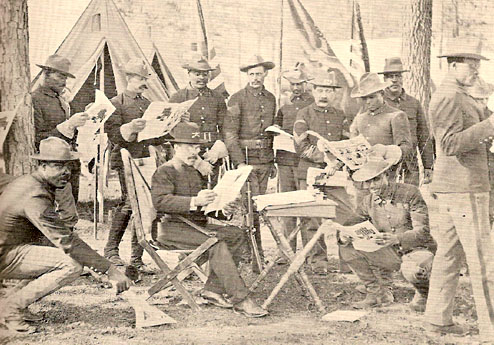

Image showing literature being distributed to the

Black troops

General:

This article addresses the difficult position help by Black troops in the U.S. Army during the Spanish American War

The Article:

America's frontier ceased to exist as a changing geographic limit by 1890. After more than 100 years of expansion on the North American continent, could the American people be expected to curtail what had become a national pastime with other world powers, particularly those of western Europe most closely identified with America, racing to attain new colonies and retain the older possessions? The fledgling country was now more than 100 years old and bursting to demonstrate its readiness to participate fully in global politics.

The American people generally supported the governmental policy of expansion. There was great satisfaction gained in forcing Great Britain to recognize American imposition in the Venezuela-British Guiana border dispute, and in enforcement of the Monroe Doctrine throughout Latin America. The Spanish presence in the Caribbean, especially on the nearby islands of Cuba and Puerto Rico, had been disturbing Americans for many years. It was predictable, then, that an insurrection by the native Cubans would find support in the United States and present an opportunity for an imperialistic adventure.

As America entered its expansionist period, the very small U. S. Army would play a very large role. After all, military might supplied the leverage politicians required in negotiating. The army, for instance, had been instrumental in subduing the native Americans on the frontier and had settled into garrisons for police duty. After 1890 the outposts were gradually withdrawn and installations were moved closer to population centers, brought into closer touch with society and topics of national interest. During the same period, the size of the army was actually increased, but the need for black soldiers to serve in the desolate western wilderness was decreased. And, with the diminishing need for black manpower, suppressed expressions of racism within the service began to reappear.

Segregation, disenfranchisement, lynching, and the rhetoric of imperialism that stressed racial superiority were becoming progressively blatant in American Society. While racism had never disappeared in America, acts of intolerance and violence toward blacks had been slowly dissipating. Now, the opportunity to colonize and exploit outside national boundaries rekindled the embers of domestic hate.

Black soldiers specifically, were targets of this reversal in race relations. On the frontier, black troops performed well and independently for over thirty years. The post civil war army had created a unique situation where black men were transported to an arena in which they could expect more equitable treatment in exchange for services. And they had made the most of it.

By 1890, the mere presence of armed black troops in many areas of the U.S. was sufficient to activate anti-black prejudices. Black soldiers returning from the plains regularly encountered attitudes which they felt should have been overcome and erased by their performance during the Indian wars, they were refused service and ordered out of "white only" restaurants, saloons, and parks, and forced to abide by Jim Crow practices on trains and trolleys.

The newly replaced obstacles encountered by black soldiers produced what came to be referred to in the black press as the "rage of the disesteemed." Black soldiers were resentful of every incident being given sensational and distorted publicity which discredited them. The treatment received by black soldiers, coupled with the absence of any opportunity to render service on the battlefield took its toll on their morale.

Obviously, the soldiers were in a more favorable position than other blacks to insist on respect and equitable treatment. They not only possessed arms and whatever legal protection was inherent in their uniforms, but there were sufficient numbers to pose a potential threat to their detractors. The threat was not one of insurrection, although that must have been a thought that occurred to blacks and whites on occasion. For the regiments to continue in effectiveness, the senior officers had to maintain high morale, discipline, and dedication to service, while retaining the ponderous trappings of racial segregation--ambiguous demands to say the least!

At times, individuals or small groups would take action in an attempt to breakdown the color barrier, but under the circumstances, black soldiers displayed remarkable restraint. One factor that helped prevent more frequent and more violent reactions on their part was the conviction that their actions had consequences for all black Americans.

The sinking of the U.S. Navy battleship MAINE, in Havana harbor, February 15, 1898, and the resulting loss of American lives gave all the cause needed to commence the war Americans, both civilian and military, seemed to want. The suddenness of the event, however, revealed a shortcoming in military preparedness for a nation with expansionist intentions.

The army totaled little more than 26,000 men and 2,000 officers. And the mass of experienced combat troops were garrisoned at numerous forts throughout the west. It was no surprise, under the circumstances, that among the first units ordered to Cuba were the four black regiments. They were selected primarily on the basis of recent experience and their record on the Plains, but there was also the judgment of the War Department that blacks were immune to the diseases of the tropics and capable of more activity in high, humid temperatures. This erroneous thinking resulted in a concerted effort to recruit blacks for the formation of more "immune" troops. Whatever the motives for mobilizing black regulars, the soldiers themselves welcomed the opportunity to demonstrate their "soldierly qualities" and win respect for their race.

Black soldiers may have had little hesitation in whole-heartedly joining the Cuban expedition, but a large segment of the black community felt differently. The anti-imperialist element was concerned about the War's impact on black Americans. Many members of this group were sympathetic with the plight of Cuba and especially with black Cubans. "Talk about fighting and freeing poor Cuba and of Spain's brutality; of Cuba's murdered thousands, and starving reconcentradoes. Is America any better than Spain? Has she not subjects in her very midst who are murdered daily without a trial of judge or jury? Has she not subjects in her borders whose children are half-fed and half-clothed, because their father's skin is black."

The anti-imperialists envisioned a war that would extend the Jim Crow empire, leaving black Americans as well as the colored population of the Spanish colonies in the same oppressed condition or worse. Only when the American government guaranteed its own minority citizens full constitutional rights, they contended, could it sincerely undertake a crusade to free oppressed people from tyranny.

The advocates of the war maintained that the black man's participation in the military effort would win respect from whites and therefore enhance his status at home. They also hoped that the islands coming under American influence would open economic opportunities for blacks and bring them into contact with predominately "colored" cultures. "Will Cuba be a Negro republic? Decidedly so, because the greater portion of the insurgents are Negroes and they are politically ambitious. In Cuba the colored man may engage in business and make a great success. Puerto Rico is another field for Negro colonization and they should not fail grasp this great opportunity."

The extreme positions of the anti and pro-war leaders did not, however, characterize the response of blacks in general. Their attitude was clearly ambivalent. A majority seemed to consider participation in the military struggle an obligation of citizenship which they would gladly fulfill if they could do so in a way that would enhance rather than degrade their manhood. They hoped that a display of patriotism would help dissipate racial prejudice against them. Unfortunately, they were never free of misgivings about a war launched in the name of humanity and waged in behalf of "little brown brothers" by a nation enamored with Anglo-Saxon supremacy.

The four black regiments were ordered to report to Chickamauga Park, Georgia, and Key West, Florida, in March and April of 1898. Although excited to leave the outposts in the West, there were also regrets. In Salt Lake City, for instance, the people demonstrated their enthusiasm and admiration for the band and men of the 24th Infantry as they lined the streets of the city to bid farewell as the regiment was leaving to join the battle in Cuba. Only two years earlier, the whites of the city had vigorously protested the stationing of black troops at Fort Douglas. Black soldiers had won the hearts of the people and, for the moment at least the people had rid themselves of racial prejudice.

Following the rendezvous at Chickamauga, the units were moved to the staging area near Tampa, Florida. For more than a month that black troops remained in the area, even their blue uniforms provided little protection from the anti-black prejudice of white soldiers and civilians alike. In the words of a Tampa newspaper, white citizens in the area refused "to make any distinction between the colored troops and the colored civilians" and would tolerate no infractions of racial customs by the colored troops."

The wait in Florida became interminable for black units camping near the cities of Tampa and Lakeland for those six weeks in May and June 1898. The 10th Cavalry, the last of the four units to arrive, was forced to find a campsite in Lakeland while the 9th Cavalry and 24th and 25th Infantry, some 3,0000 strong, encamped near Tampa. Racial tension was nothing new for the southeastern United States, but the sudden arrival of blacks unaccustomed to blatant discrimination created an explosive atmosphere. Shortly after their arrival in Lakeland, black troops found themselves in a confrontation with a white antagonist that ended with the man's death and the arrest of two black soldiers. "some of our boys, after striking camp, went into a drug store and asked for some soda water. The druggist refused to sell to them, stating he didn't want their money, to go where they sold blacks drinks. That did not suit the boys and a few words were passed when Abe Collins came into the drug store and said: "You d____niggers better get out of here and that d_____quick or I will kick you B__S___B____out," and he went into his barbershop which was adjoining the drug store and got his pistols, returned to the drug store. Some of the boys saw him get the guns and when he came out of the shop they never gave him a chance to use them. There were five shots fired and each shot took effect." In Tampa, conditions were no better, erupting in violence on the eve of embarkation for Cuba and sending nearly 30 black soldiers to the hospital.

Black units left Tampa in mid-June "Glad to bid adieu to this section of the country" and hoping "to never have cause to visit Florida again." Sailing from the west coast of Florida, the flotilla of 32 ships carrying nearly 17,000 men landed in near Santiago, on the southeastern tip of Cuba, on June 22 1898. Two days later, the Spanish were engaged at Las Guasimas. The 10th Cavalry, in reserve as the battle began, participated full and was lauded by officers who witnessed their assault on fortified enemy positions. The success of the black troops might well have served them better and their feats heralded had it not been for the participation of the 1st Volunteer Cavalry, better known as Theodore Roosevelt's "Rough Riders."...The morning of June 24 there were three columns started West, first the 1st Volunteer (taking the) bridle path on the very comp of the mountain, where the underbrush was so thick it was impossible to walk only in single file; next, the 1st United States Regular Cavalry, going over a rough and irregular wagon road, running north or parallel with the route taken by the Rough Riders, the two roads making a junction about four and one-half miles west of here, and the third column, the 10th United States Cavalry, taking a route about a mile or more still further north where there was no road at all. It was intended that the three commands should move as nearly abreast as possible, but the difficulties the 10th Cavalry had to contend with in advancing were not taken into consideration, so they were twenty to thirty minutes behind on getting into action They all took up the march as above, advancing as blind men would through the dense underbrush."

The first column, the Rough Riders, was the first to strike the enemy in ambush 500 yards east of the junction of the two roads mentioned, receiving a volley that would have routed anybody but an American. The first regulars, hearing the music as they called it, hurried forward to join in the dance, and awoke a hornet's nest of Spaniards on the left, north of the party engaging the Rough Riders, and had more music than they could furnish dancers for. But, to the credit of the uniform and the flag, there if no account of either column giving an inch. They advanced sufficiently to come into line, and holding their ground until the much abused and poorly appreciated sons of Ham burst through the underbrush, delivered several volleys and yelling as only black throats can yell, advanced on a run. Their position being still further to the north and opposite the left flank of the Spaniards, they could not stand it any longer, but broke and ran, and did not make a decided stand until they faced us at San Juan...When the battle closed June 24 there were nineteen or twenty killed, but only one of them was colored."

A week later, the expeditionary force launched a two-pronged attack intended to secure the outpost at El Caney and the entrenchments on San Juan Hill. The two forces were to gain their objectives and join together for the final assault on Santiago. Troopers from the 25th Infantry acquitted themselves well at El Caney and were among the first to reach the outpost after heavy fighting. Meanwhile, the 24th Infantry and the 9th and 10th Cavalry regiments were establishing a reputation for "themselves as fighting men" at San Juan Hill once more in the shadow of the more heralded, but no more effective, Rough Riders. As the Rough Riders advanced up San Juan Hill they found themselves attacked from all sides and in great danger of being cut to pieces. The black troops of the 9th and 10th Cavalry were some distance away when the word reached them. They went to help on the run. Leaving a trail of dead and wounded left behind, the troopers of the 10th Cavalry advanced under heavy fire, according to a New York reporter, "firing as they marched, their aim was splendid. Their coolness was superb and their courage aroused the admiration of their comrades."

It was this action that led a grateful Rough Rider corporal to proclaim, “If it hadn't been for the black cavalry, the Rough Riders would have been exterminated." Five black soldiers of the 10th Cavalry received the Medal of Honor and 25 other black soldiers were awarded the Certificate of Merit. For action on July 1, 1898, Private Conny Gray Co. D 25th Infantry, 1st sergeant John Jackson, Troop C, 9th cavalry, Sergeant Elisha Jackson, Troop H, 9th cavalry, corporal George W. Pumphrey, Troop H, 9th cavalry, Private James Bates, Troop H, 9th cavalry, Private Edward Davis, Troop H, 9th cavalry, 1st sergeant Charles W. Jefferson, Troop B, 9th cavalry, Saddler sergeant Jacob C. Smith, Troop C, 10th Cavalry, 1st sergeant Adam Houston, Troop C, 10th Cavalry, corporal John Walker, Troop D, 10th Cavalry, Private Luchious Smith, Troop D, 10th Cavalry, 1st sergeant Peter McCown Troop E, 10th Cavalry, sergeant Benjamin Fasit, Troop E, 10th Cavalry, sergeant Ozrow Gather, Troop E, 10th Cavalry, sergeant John Graham, Troop E, 10th Cavalry, sergeant William Payne, Troop E, 10th Cavalry, corporal Thomas H. Herbert, Troop E, 10th Cavalry, trumpeter Oscar N. Oden, Troop I, 10th Cavalry, sergeant James Satchell, Co. A, 24th Infantry, Private Scott Crosby, Co. A, 24th Infantry, Private Loney Moore, Co. A, 24th Infantry, corporal Richard Williams, Co. B, 24th Infantry, sergeant John T. Williams, Co. G, 24th Infantry, corporal Abram Hagen, Co. G, 24th Infantry,corporal Peter Jackson, Co. G, 24th Infantry, corporal William H. Thornton Co. G, 24th Infantry, Artificer Jesse E. Parker, Co. D,24th Infantry, for action June 24, 1898, Private John A. Humphrey, Troop I, 10th Cavalry. Cuba. In 1922 the War department began systematically reviewing official reports and records and 8 other black soldiers were awarded the Silver Star Citation and Medal's, Presly Holliday, Isaac Bailey, John Buck and Augustus Walley of the 10th Cavalry, George Driscoll, Robert L. Duvall, Elbert Wolley and Richard Curtis of the 24th Infantry.

At San Juan Hill alone, there were 21 who received citations for gallantry 13 received the Certificate of Merit and one Medal of Honor recipient 8 others the Silver Star. But it was not all glory: "We had been on the hill about three hours and my gun was almost red hot. I had fired about 175 rounds of ammunition, and being very thirsty, I gladly accepted the detail, as the hill was ours then and we had been shooting at nothing for about an hour. what a sight was presented as I recrossed the flat in front of San Juan. The dead and wounded soldier! It was indescribable! One would have to see it to know what it was like, and having once seen it, I truly hope I may never see it again....before sunrise the battle was raging furiously. It lasted all day with no intermission, until dark. Everybody being his own cook, and not having anything to cook, I had a very simple diet that day. Almost all the army had the same--breakfast, canteen half full of water: dinner, full canteen of water; supper, the empty canteen. We were relieved after dark by a part of the 71st, and to the rear to get sleep and rest. In about one or two hours, at 8 or 9 o'clock, the Spanish made an assault on our position, which was repulsed with terrible losses to them. The casualties were light on our side, but we learned since that it cost the Spaniards more than 600 men in attempting to drive us from San Juan. They found the Yankee wide-awake and not giving an inch. The attack lasted about forty-five minutes, and while it was going on it seemed ten times worst than the battle of the day before. We were finally allowed to return to position in reserve and go to sleep." While most black troops were participating in the actions around Santiago, Troop M of the 10th Cavalry had joined General Gomez of the Cuban Army and took part in several actions. Their activities, once again unheralded, earned the Congressional Medal Honor for four of its enlisted men. "These soldiers of Troop M were isolated from other American forces about three months while they fought with the Cuban insurgent army, they participated in several notable engagements, these cavalrymen would be the only mounted troops during the Cuba campaign, four privates, Dennis Bell, Fitz Lee, William H. Thompkins and George H. Wanton, won particular distinction for staging a daring rescue operation on June 30, 1898 at Tayabucoa. But here again, there was an obstacle to overcome. "The whole company came near getting massacred on account of his (1st lieutenant Carter P. Johnson), getting drunk. After the Cubans and his command had taken a fort and a block house, he got a barrel of rum, got drunk, pulled down the Spanish flag and ran up his blouse as the American flag. He was given just one-hour to leave the fort. He ordered his men to fire upon the Cubans, which they refused to do, as they would have been massacred had one shot been fired."

The Spanish fleet in the Caribbean was destroyed by American ships on July 3, 1898, forcing surrender of the islands on July 16. By this time, over 4,000 men were hospitalized with dysentery, yellow fever, typhoid, and Malaria. Black soldiers once more made testament to their commitment to the military effort as the 24th Infantry went to the aid of the hospital in Siboney after the assignment had been turned down by eight white units. The tropical conditions, lack of proper nutrition and medical facilities, and the reluctance to immediately return the troops home once the war was over cost the lives of some 5,000 men fewer than 400 lost their lives in combat. "We have thirty-eight men present in the troop, of which nineteen are down with fever. Now we are almost naked, no medicine, not much to eat, hot water to, drink, sleeping on the bare ground, no papers of any kind."

Briefly in the late summer of 1898, the black regiments enjoyed the status of heroes, receiving recognition from whites as well as blacks. The war correspondent Stephen Bonsal wrote."The services of no four white regiments can be compared with those rendered by the four colored regiments. They were at the front at Las Guasimas, at El Caney and at San Juan, and what was the severest test of all, that came later, in the yellow fever hospitals."

Chaplain Allen Allensworth and the 24th Infantry regiment were at Fort Douglas, Utah. At the very outset Allensworth addressed the issue of Black manhood. After they received orders to proceed to Florida, the regiment was marched from their barracks into a formation near the regimental commander's headquarters to hear an address by Chaplain Allensworth. He spoke to the troops, one company at time, saying: "Soldiers and comrades, Fate has turned the war dogs loose and you have been called to the front to avenge an insult to our country's flag. Before leaving I will say to you, ‘Quit yourselves like men and fight.’ Keep in mind that the eyes of the world will be upon you and expect great things of you. You have the opportunity to answer favorably the question, ‘Will the Negro fight?’ Should you be ordered to charge the enemy, as your brothers then said as they charged, ‘Remember Fort Pillow,’ so when you are ordered to charge, say to your comrades, ‘Quit yourselves like men and fight,’ and Remember the Maine!" Chaplain T. G. Steward expressed pride in the Black regiments mobilized for service in Cuba and believed that their performance would improve the condition of "the Black man of the south." In his many letters to the Cleveland Gazette, between May 1898 and July 1901, Steward frequently addressed the racial issue, commenting on the racial customs he witnessed in the South, he remarked: "A glorious dilemma that will be for the Cuban Negro, to usher him into the condition of the American Negro." Whenever Steward encountered discrimination, he did not back away.

With the movement of Black troops South during the War with Spain Chaplain Prioleau, started addressing the racial issue and over the next few years became quite vocal about it. In a letter to the Cleveland Gazette, Prioleau talked about the reception of Black regulars in the South he said: "The prejudice against the Negro soldier and the Negro was great, but it was of heavenly origin to what it is in this part of Florida, and I suppose that what is true here is true in other parts of the state. Here, the Negro is not allowed to purchase over the same counter in some stores that the white man purchases over. The southerners have made their laws and the Negroes know and obey them. They never stop to ask a white man a question. He (Negro) never thinks of disobeying. You talk about freedom, liberty etc. Why sir, the Negro of this country is freeman and yet a slave. Talk about fighting and freeing poor Cuba and Spain's brutality; of Cuba’s murdered thousands, and starving reconcentradoes. Is America any better than Spain? Has she not subjects in her midst who are murdered daily without a trial of judge or jury? Has she not subjects in her own borders whose children are half-fed and half-clothed, because their father's skin is Black. "Yet the Negro is loyal to his country's flag. O! he is a noble creature, loyal and true, forgetting that he is ostracized, his race considered as dumb as driven cattle, yet, as loyal and true men, he answers the call to arms and with blinding tears in eyes and sobs he goes forth: he sings "My Country 'Tis of Thee, Sweet Land of Liberty," and though the word "liberty" chokes him, he swallows it and finished the stanza "of Thee I sing."

Chaplain Prioleau, was on recruiting duty for the 9th Cavalry, while the regiment was away fighting in Cuba. In another letter to the Gazette, he calls attention to the cruelties and ironies spawned by racial prejudice, also he reveals a similar attitude that chaplain Plummer, displayed not many years before: "Tuskegee, Alabama, normal and industrial institute furnishes the town with electricity. Think of it! The slaves of Alabama furnishing material and intellectual light for their former masters. Yet when an officer of the United States Army, a Negro chaplain, goes in their midst to enlist men for the service of the government, to protect the honor of the flag of his country, and this chaplain goes on Sunday to M.E. Church (White) to worship God, he is given three propositions to consider, take the extreme back seat, go up in the gallery or go out. But as we were not a back seat or gallery Christian, we preferred going out. We did not fail to inform them on the next day that the act was heinous, uncivilized, unchristian, un-American. We were informed that niggers have been lynched in Alabama for saying less than that. We replied that only cowards and assassins would overpower a man at midnight and take him from his bed and lynch him, but the night you dirty cowards come to my quarters for that purpose there will be a hot time in Tuskegee that hour; that we were only three who would die but not alone. We stayed there ten days, enlisted 34 men."

Later that month Prioleau, wrote still another letter to the Gazette, in this letter he points out the difference in the reception given white soldiers and those of his own regiment. Prioleau was keenly aware that the war with Spain had failed to dissipate Negro phobia as he called it, as some Blacks had predicted it would. In his view, "hatred of the Negro" is no longer confined to the South, it had become a national rather than a sectional phenomenon: "While the cheers and the "God bless you" were still ringing in our ears, and before the warm handshakes had become cold, we arrived in Kansas City, Mo., the gateway to America's hell, and were unkindly and sneeringly received. Yet these Black boys, heroes of our country, were not allowed to stand at the counters of restaurants and eat a sandwich and drink a cup of coffee, while the white soldiers were welcomed and invited to sit down at the tables and eat free of cost. You call this American ‘prejudice.’ I call it American ‘hatred’ conceived only in hellish minds. Why, sir this thing is getting worse every day. An expression of Senator Tillman's June speech is: ‘Down with the niggers,’ but if we must tolerate them, give us those of mixed blood. And yet if a Negro man marries, or even looks at a white woman of South Carolina, he is swung to the limb of a tree and his body riddled with bullets. It seems as if there is no redress in earth or Heaven. It seems as if God has forgotten us. Let us pray for faith and endurance to ‘Stand still and see the Salvation of God.’"

While Chaplain Steward was stationed in the Philippine Islands a white medic refused to salute him. How did he react? Steward said, "I have found it necessary to round up a few white soldiers for disrespect since I have been here. In every case I have succeeded in bringing them to terms in the shortest sort of order. I was coming away from the a hospital one Sunday and the corps man failed to salute me. I turned and followed him to the office and said to the steward: ‘Who has charge here?’ He arose, and saluting promptly, replied, ‘Major Keefer, sir.’ ‘I want to see that young man,’ said I. ‘Call him.’ He did so, and the man came up and saluted as humbly as need be. I gave him a word of instruction, and that cured everybody around the hospital.”

”The other day three volunteers riding in a hack (Forty-third volunteers) passed me as I was riding the other way and indulged in some vile cursing at my expense. They did not know me as well as they thought they did. I ordered my driver to turn and follow them, and soon overtaking them, I ordered their driver sternly to halt, a command which he obeyed instantly. I then got out of my carriage and read them a lecture, they denying they had said anything disrespectful and begging me to let them pass on. I subsequently reported the affair to their colonel, not desiring any action to taken as I had not sufficient proof; but it helped them. So, I have found it necessary to be a little exacting and have tightened up the reins around me a little." A year later on his return to the United States on an Army transport with his son, also an officer, the dining room steward attempted to relegate them to a side table. Chaplain Steward refused to sit there and brought the matter to the attention of his regimental commander; the colonel settled the matter by inviting him to dine at his table and seating his son with the junior officers.

Prioleau made much of the racial affinity between Black Americans and the "dark skinned people" of the Philippines, but by the summer of 1901 his attitude began to change, as the condition of Blacks at home continued to worsen. In a letter to The Colored American Magazine of Washington D.C., he expressed some of his fears that the United States was less concerned with the welfare of its own Black citizens than with that of the people of the colonies. Perhaps more graphically than anyone else Prioleau, expressed the attitude of most Black Americans, when he suggested that the generosity of the U.S. might enable the Filipino to "Outstrip the Negro." His fear was that the Brown man of the Pacific, would become “America”s China baby,” while the Black citizen continued “to be the ‘rag’ baby of the republic.

Chaplain Anderson, was the only Black chaplain to serve in Cuba during the war. Lieutenant Colonel T. A. Baldwin, of the 10th Cavalry wrote this about Anderson, in 1899, "After being relieved by Major Kelley, Chaplain Anderson on his own request was ordered to join his regiment in Cuba and on the 24th day of July reported for duty. He at once applied himself to assisting in the relief of the many fever patients then in the regiment by visiting and nursing the sick and cheering them by his Christian example and fortitude even after he was sick and suffering himself and effected much good."

Chaplain Prioleau was on his way to Cuba with the 9th Cavalry but contracted malaria in Tampa just before his departure and remained in the states. When he recovered sufficiently, he was placed on recruiting duty for his regiment in Tuskegee, Alabama, and in his home town of Charleston, South Carolina. Though recruiting was not a customary duty for a chaplain, his regiment, as well as other regiments, needed men to meet its authorized wartime strength; it was therefore an important duty. Chaplains Steward and Allensworth were on regimental recruiting duty for the duration of the Cuban campaign, both men served in their home town areas, Steward in Dayton, Ohio, and Allensworth in Louisville, Kentucky. In that capacity Allensworth was especially successful. While awaiting his orders at Fort Douglas, Utah, after his unit, the 24th Infantry, had departed, he recruited in the Salt Lake City area for a regiment composed of white troops. After he received his orders, he recruited 465 men, which put the strength of the 24th at 1,272. Within six months after the Spanish-American War ended, Three of the Black regiments and a part of the fourth were sent to the Philippine islands for duty. Chaplains Allensworth, Steward and Piroleau went with their regiments to the islands. Chaplain Anderson, served with his regiment in Cuba as part of the occupation forces from (1899-1902), and with the regiment in the Philippines Islands (1907- 09).

Shortly after the end of the Spanish-American War a decline began in the status of Black serviceman. White sentiment ran against Black soldiers; too much apparently had been made of their success, causing them to forget their subservient "place. "Even Theodore Roosevelt, who had been a supporter of Black soldiers, reversing his earlier praise, stated that Black soldiers were peculiarly dependent upon their white officers and Black noncommissioned officers generally lacked the ability to command and handle the men like the best classes of whites. Roosevelt apparently was bowing to the pressures of public opinion.

Actually, the status of Black regulars had begun to slowly erode as early as 1890 when the army expanded but did not expand the opportunities for Blacks. Moreover, the emphasis had shifted to education and technical skills, and it was widely held that Blacks as a rule lacked the innate intelligence to assume these new responsibilities.

At the close of the century, however, Black servicemen had become impatient with the long-standing policy of limited opportunities, discrimination, and paternalistic white officers. Chaplain Steward's comments revealed the deepening dissatisfaction of Black servicemen. "The colored American soldier, by his own prowess, has won an acknowledged place by the side of the best trained fighters with arms," he said. "In the fullness of his manhood he has no rejoicing in patronizing paean, the colored troops fought nobly, nor does he glow at all when told of his 'faithfulness' and devotion to his white officers, qualities accentuated to the point where they might well fit an affectionate dog." The military refused to meet the growing expectations of its Black soldiers.

Throughout the period from the end of the Spanish-American War to the beginning of World War 1, the notion of Black men as officers was largely rejected by the military who reflected the popular stereotypes of Black inferiority. To the call for increasing the number of Black commissioned officers, a writer to the Army and Navy Journal argued that experience up to that time had not justified the request. Education could not remove innate inferiority. The ability to lead comes from generations of cultivation, and the American Negroes were descendants of weak African tribes easily overcome by "vigorous neighbors." He concluded by reaffirming the long-held view that Blacks may make excellent soldiers, "but the qualities that make a good soldier and those required for an officer are not necessarily the same." On alleged racial inferiority, Chaplain Steward offered a rebuttal using Black soldiers as his evidence. Even though he pointed out that American soldiers were classed as colored and white, the expectations, feeding, clothing, and general treatment were the same. The military, he contended, was the best place to evaluate the subject. Comparing regiment by regiment for considerable periods of time there is no evidence of physical or moral inferiority on the part of the Negro. And it is fact that the Black regiments have fewer court martial cases, fewer desertions and less alcoholism was clear, save individual differences, but "regiment with regiment, company with company" there was equality. Chaplain Steward made this comment about race and the color question in 1901: "Nothing is clearer than the fact that the great color question is dividing the world. Just as it is wicked to be Black in America. I fear the day will dawn when it will be wicked to be white. Three fourths of mankind are surely awakening. The World's Negro Congress is but a straw. The coming people are those of Asia and Africa. Japan has already shown what can be done; and the Filippinos, Chinese, and people of India are sure to emerge, sooner or later."

Convinced that they had demonstrated their value as combat troops and imbued with a new sense of self-confidence, black soldiers expected to be rewarded commensurate with their performance, nothing less than officers’ commissions. The failure of the War Department to extend such recognition in the regular army was vigorously protested by black veterans of the Cuban campaign and especially by black civilians. Their contention was that even if the law establishing the black regiments required white officers, it was the duty of Congress and the War Department to have the law changed. The promotions for some non-commissioned officers and the granting of commissions in the volunteer service for those black regulars who displayed conspicuous gallantry in Cuba did nothing to dispel the disappointment and disillusionment. "Will this government recognize and reward the brave non-commissioned officers of the 10th cavalry for the gallantry who, when the white commissioned officers were either killed or wounded and could go no further, took command. When the leadership fell upon them, did they cry out in despair, ‘I want a white man to lead me?’ No! The troops had confidence in their Negro leaders; they did not become demoralized but marched on to a glorious victory under the leadership of Negroes whose names should go down in history. These men showed that they could be depended upon at a critical moment and why not now?

While the states were mobilizing black volunteers in the summer of 1898, Congress authorized the War Department to organize ten additional volunteer regiments under its immediate direction. These additional black units were the 7th, 8th, 9th, and 10th Volunteer Infantry regiments, and were recruited from the black population in the South and the Ohio Valley. In response to the demand for black officers, the War Department commissioned blacks as lieutenants in the line companies of these so called "immune" regiments. The term of service for Volunteers, including the black regiments, was of short duration. In most instances, it was about one year.

Benjamin O. Davis Sr., began his long and distinguished military career as an officer of the 8th United States Volunteer Infantry, in July, 1898. For some of those black officers like Davis, who had been civilians learning and teaching occurred simultaneously. In Davis’ Company G, Captain Palmer (white) had no military training, and Lieutenants Davis and Minkis had merely been high-school cadets. Although Davis was given the job of training the company in close order drill, he relied on the help of 1st Sgt Calvin Tibbs, a veteran of five years in Troop L, Ninth Cavalry. Another black soldier who helped Davis in those early months was 2nd Lieutenant Andrew J. Smith, who prior to his commissioning had served for twenty-eight years as a non-commissioned officer with the Twenty-Fifth Infantry. Davis learned much about the customs of the service and the application of military principles from Smith.

One Soldier of the 6th Virginia Volunteers had this to say about the attitude of the white commander of his regiment. "When the second call was made in 1898, there was talk of white officers for the 6th, the objections were so strong, the War Department allowed the Negro Militia to have their own officers. 1st Lieutenant R.C. Croxton, of the regular army was commissioned Lt. Colonel, commanding. At Camp Corbin, Va., when the 6th, was organized, all seemed to be working smoothly. At Knoxville, Tenn., it was apparent that Lt. Col. Croxton had little use for his Negro Officers. Many times I heard him reprimand ‘Captains’ or ‘Lieutenants’ in front of the men. After being in Knoxville for a few days, we were told that the Major of the 2nd Battalion, 5 Captains and 3 or 4 Lieutenants had been ordered to take examinations. They promptly resigned exactly what the Lt. Col. wanted.” The Officers said they passed the State Board at Richmond. White officers were brought in the replace those blacks who resigned. Allen went on to state" From my own experience and what I have read, white officers are proud to command Negro soldiers. What hurts a white officer, is seeing a Negro wearing ‘shoulder straps’ Thanks to heaven, all changed since World War 1."

During 1898-1899, the 9th Volunteer Infantry, one of the "immune" regiments along with two black state units the 8th Illinois and the 23rd Kansas, performed garrison duty in Cuba. "When we are in Santiago we are reminded so much of home. There is a hotel there called the American, run by an American who is from St. Louis, Mo. The first time I was there I went to that hotel with Captain Hawkins of Atchison, who is very light in color. They thought he was white so said nothing to him, but the proprietor was going to stop me. He said his boarders and white customers objected to eating with colored men and that he could not afford to ruin his business by accommodating me. I told him I was an American officer and had always associated with gentlemen all my life and did not propose to disgrace myself or my shoulder straps eating at a side table or in a side room to please a few second class white officers who never had money enough to take a meal in a first class hotel until they became officers in the volunteer army of the United States during the present war; I ask no special privileges, but would have what was due me as an army officer or know the reason why; that he need not think that we colored soldiers who spilled so much of our precious blood on the brow of San Juan Hill that it might be possible for him and other Americans to safely do business, and are standing now with bayonets or guns as sentinels to protect them in that business, were to allow any discrimination on account of our color; and all I wanted to know was whether or not he was going to feed me.

The dining room was full of officers and others, and you could have heard a pin fall while I was talking, and while the proprietor was finding something to say an officer whom I later found out to be General Ewers of military district no. 1, got up from the table, walked over to me and grasped my hand and said, "Come, Captain, take my seat; and you, Mr Hotel Proprietor, get him some food and get it quick; and I don't want to hear any more of this d____n foolishness with these officers of mine.! I was a little king there in about a minute..."

Black volunteers who remained in the United States were shuffled from camp to camp and subjected to discriminatory treatment by whites, especially civilians. Disillusioned with military service as a means of improving the condition of their race, most black volunteers welcomed the mustering out of their units early in 1899. Most of the regular army non-commissioned officers who had accepted commissions in the volunteers returned to their regular units with their previous rank. The enlisted men who remained in the regular army units fared no better. This was indicative of the comments made at the time: "While the cheers and the ‘God bless you’ were still ringing in our ears, and before the warm handshakes had become cold, we arrived in Kansas City, Mo., the gateway to America's hell, and were unkindly and sneeringly received...these black boys, heroes of our country, were not allowed to stand at the counters of restaurants and eat a sandwich and drink a cup of coffee, while the white soldiers were welcomed and invited to sit down at the tables and eat free of cost."

In some instances, the bigots were not content to enforce Jim Crow customs. "Private John R. Brooks, Troop clerk of H Troop and Corporal Daniel Garrett. were returning to their camp about 9 or 9:30 p.m. after visiting friends. They were waylaid and shot down, Private Brooks being killed instantly. Corporal Garrett died on the 13th inst ‘Horse’ Douglas, colored, was captured as he was running past a policeman with a pistol in his hand Some low scoundrel put out a reward for every black 10th Cavalryman that was killed. A black man tried to commit the crime... a soldier placed a pin knife at the throat of the would be murderer and made him give his pistol up, which he turned over to his Captain. This man called the next day for his pistol, but the Captain refused to give it up, but otherwise he took no action in the matter. This is the kind of protection men in the 10th Cavalry receive. This man even made a statement that there was a reward on the head of every 10th Cavalry man. Are we to stand by and see our comrades foully murdered? James Nealy a Private of the 24th Infantry was Shot and killed in Hampton, GA, because he asked for a glass of soda water: This business is getting serious, and the end is not far off. No use to look to the government. It has been slumbering for some time. Colored men must protect themselves, if they hang for it. Lynch law must go!" In some instance the men took the law into there own hands Sergeant John Kipper of Co A 25th Infantry was sentenced to life in prison for leading a mob of Negro soldiers against an El Paso, TX, police station, 17 Feb 1900, and for murder of policeman Newton Stewart.

Marvin Fletcher, “The Black Soldier and Officer In the United States Army, 1891-1917.,"University of Missouri Press, 1974.

The Kansas City Daily," 1904. News clipping in author's collection.

Martin E. Dann, "The Black Press 1827-1890," G.P. Putnam's Sons, New York, 1971.

AGO 73129, NA, RG 94, The Afro-American Sentinel (Omaha, Nebraska), 2 April 1898; SA War Invest, 2:871 U.S., Congress, House, Committee on Military Affairs, House Miscellaneous Documents, No. 64, 45th Congress, 2nd Session, 1877, VI, 20.

"Colored American," newspaper (Washington D.C.), August 13, 1898.

Tampa Morning Tribune, May 5, 1898.

Springfield Illinois Record, June 25, 1898.

Washington DC Evening Star, August 24, 1898, September 17, 1898.

Richard Harding Davis,"The Cuban and Porto Rico Campaigns," (New York: Charles Scribners Sons, 1904).

"The Santiago Campaign: Reminiscences of the Operations for the Capture of Santiago de Cuba in the Spanish-American War, June and July, 1898 (Richmond: Williams Printing, 1927.

Baker, Edward L. ,Jr. QM Sgt U.S. Army,. VA Pension File XC 2715800,

War Department GO# 34, 1924. GO #14, 1924. GO #21, 1925.

E. N Glass,"History of the Tenth Cavalry," Tucson, ACME Printing 1921,

Unsigned, Illinois Record, October 8, 1898.

Illinois Record, September 3, 1898, December 3, 1898.

H. Steward,"Colored Regulars," Philadelphia, A.M.E. Book Concern 1904.

"The Nation," LXVI (May 5, 1898), p. 335

"The Cleveland Gazette," May 13, 1898, May 21, 1898, October 1, 1898, October 22, 1898, April 21, 1900.

Steward, "Fifty years in the Gospel Ministry,"

"Colored American Magazine," July 13, 1901

"Indianapolis, Freeman," January 25, 1902.

William T. Anderson to the Adjutant General, Department of Dakota, 10 May 1898, Selected ACP, W.T. Anderson, RG 94, NA, William T. Anderson to George A. Myers, Cleveland, Ohio, 4 May 1898, 3 June 1898, George A. Myers Papers, Box 6, Folders 3 nad 4, Ohio Historical Society, Columbus, Ohio.

Marvin A Kreidberg and Merton G. Henry, "History of Military Mobilization in the United States Army, 1775-1945,"

Theophilus G. Steward to the adjutant General of the Army, Washington, D.C., 5 July 1898, Sleeted ACP, T.G. Steward, RG 94, NA; Special Orders No. 180, Adjutant General's Office, War Department, Washington, D.C., 2 August 1898; Alexander, Battles and Victories.

Foner, "Blacks and the Military in American History," p. 81.

Carroll, "The Black Military Experience in the American West," p. 525.

"Army and Navy Journal," 37, September 23, 1899. p. 238.

T. G. Steward, "The Negro Not Inferior," Army and Navy Journal 41, November 21, 1903, p 290.

John E. Lewis, to the editor Illinois Record, August 13, 1898.

Cashin, Alexander, Anderson, Brown, Bivins,"Under Fire with the 10th Cavalry," F. Tennyson Neely, Publisher, New York.

Marvin E. Fletcher, "America's First Black General, Benjamin O. Davis, Sr. 1880-1970," University Press of Kansas, 1989.

John H. Allen, Army service Experiences Questionnaire ,"Spanish-American War. Philippine Insurrection, and Boxer Rebellion Veterans Research Project, "Department of the Army U.S. Army Military History Research Collection Carlisle Barracks, Pa. 1969.

John E. Lewis, to the "Illinois Record" December 3, 1898.

Richmond Planet, 27 Aug 1898.

ANJ 37 (12 May 1900): 869.

Neely, F. Tennyson, Neely's Panorama of Our New Possessions. (New York: December, 1898)(image source).