How Was the Spanish American War Financed?

By Patrick McSherry

Please Visit our Home

Page to learn more about the Spanish American War

General:

How was the Spanish American War funded, or, in

other words, how did we pay for the Spanish American War? This article

addresses the means used to finance the cost of the Spanish American

War.

The Article:

So exactly how does a nation finance an event like the Spanish

American War? Does it take out a mortgage on some already paid-off

battleships? Call Quicken Loans or Lending Tree? Hold a very large bake

sale? Sell the war’s film and television rights as is done to help pay for

the Olympics? Hope that an unknown relative passes away and leaves the

country a large inheritance? No, none of these will meet the needs, though

the latter may help indirectly as we will see below.

Snarky comments aside , how does the government usually finance a war? The

answer is obvious - through taxation and loans. The larger questions are

really who gets taxed and how is the decision to tax made palatable to the

nation.

Only five days after war was declared, the necessity of how to fund it was

taken up by the U.S. Congress. More specifically, on April 26, the House

of Representatives Ways and Means Committee took up debate on a bill

proposed by the head of the committee, Maine Congressman Nelson Dingley

Jr. Newspapers noted that the debate did not have the partisan

rancor which had been common as both sides agreed for the need for funds

to prosecute the war effort. As always, the challenge was to determine how

it could be done with the least political backlash.

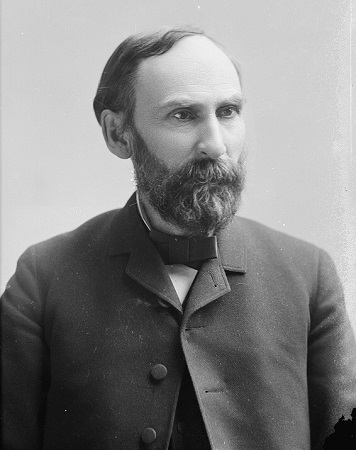

Nelson

Dingley, Jr., Chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, who

introduced the War Revenue Act. Dingley

was a former governor of Maine. He died in

1899, and did not see the repeal of the

Act (Source: Library of Congress)

After two days of debate, the bill was

sent to the U.S. Senate’s Finance Committee, and then to the Senate

itself. Eventually, after twenty days of debate, the amended bill passed

the Senate and went back for reconciliation with the House of

Representatives.

On June 13, 1898, as the Fifth Army Corps was already embarking on

transports to depart for the invasion of Cuba, Congress passed “An Act to

Provide Ways and Means to meet War Expenditures, and for Other Purposes,”

more commonly known as the “War Revenue Act of 1898” The plan of the tax

act was a six-pronged effort to raise taxes, but to simultaneously avoid

taxing individuals directly to make the bill more palatable. The

six-pronged approach was based on the following:

1. Tax manufacturers and suppliers of vices

2. Tax manufacturers and suppliers of luxuries.

3. Require official documents to have a purchased

revenue stamp

4. Institute a graduated estate tax or “death tax.”

5. Tax manufacturers of a few essentials

6. Loans and the issuing of war bonds

When looking at the amount of the taxes, it may be useful to keep in mind

the value of a dollar in 1898 is roughly equivalent to 30.98 dollars in

2020.

Taxes on Vices

First, some vices were targeted for taxation, as if often done. Beer,

lager, ale , cigars, snuff, and cigarettes were taxed. However, rather

than taxing the end user directly, the manufacturers and sellers of these

items were taxed. The politicians were in the clear as the manufacturers

had to decide whether to pass the costs along to the public or not – the

‘ol “we didn’t raise your taxes, we raised taxes on the evil big

businesses” ploy.

Brewers of beers, ales, lagers, and other fermented beverages were taxed

at a rate of two dollars for a standard thirty-one gallon barrel.

Manufacturers of tobacco products were taxed at a rate of twelve cents per

pound. Cigars manufacturers were taxed at a rate of $3.60 per thousand

cigars that weighed more than three pounds per thousand, and only one

dollar per thousand for cigars weighing less than three pounds per

thousand. Cigarette manufacturers were taxed at a rate of $3.60 per

thousand. In addition, those dealing in tobacco products were additionally

taxed.

Bowling alleys and billiard halls were also taxed, at a rate of five

dollars per alley or table respectively.

Taxes on Luxuries

Imported tea was taxed at a rate of ten cents per pound.

Some of the small luxuries of life were also taxed, adding to the cost of

a family outing. The proprietors of theaters, museums and concert halls in

cities with a population of over twenty-five thousand people were required

to pay one hundred dollars. Proprietors of circuses – which were defined

as buildings or tents where feats of horsemanship, acrobatic sports or

theatrical performances were held – had to also pay one hundred dollars.

And if the circus moved to a new location in another state, it would have

to pay again in that state. Also, it was unclear that if a circus used

more than one tent if they had to pay the tax for each tent.

Should a person decide to go to the local pawnbroker in an effort to pawn

something to get some cash to pay for their increased costs, they may have

found themselves getting slightly less than expected as the pawnbroker was

faced with a tax of twenty dollars.

Telephones were new at the time, and few people had them. The War Revenue

Act taxed the luxury of phone calls. Telephone calls costing fifteen cents

or more were taxed one cent.

A

cartoon from 1898 suggesting a new tax - taxing single men to

support those who fight the "war of

matrimony" (Source Library of Congress)

Revenue Stamp Taxes

Revenue stamps were introduced. The stamps, which had to be purchased from

the government were required on all sorts of documents, such as bonds,

stocks, insurance certificates, conveyances and deeds, telegrams,

certificates of deposits, patents, trademarks, letters of credit, wills,

bills of lading, liens, powers of attorney and even tickets for ocean

travel to foreign countries. In short, any kind of official paperwork

required the purchase of a stamp, the cost of which varied by the type of

document.

Also requiring stamps were any type of packet, box or vial of pill,

lozenge, liquid or medical preparation. Perfumes and cosmetics also fell

under this requirement as did chewing gun and wine. Of course, the stamps

had to be purchased by the manufacturers of these items. The manufacturer

could pass that cost along to the customer or take a loss in profit.

Estate Taxes (“Death tax”)

Though estate taxes – better known as “death taxes” - existed

previously, the War Revenue Act instituted a system whereby those

receiving an inheritance – a portion of a deceased person’s money,

property, stocks, etc. – paid a tax on the inheritance with the amount of

tax depending on how closely the person receiving the inheritance was

related to the deceased, as follows:

1. If the person was a lineal descendant of the

deceased, or was the brother or sister of the deceased, the person paid a

tax of $0.75 per $100 inherited.

2. If the person was a descendant of the deceased’s

brother or sister, the tax paid was $1.50 per $100 inherited.

3. If the person was an aunt or uncle of the deceased,

or the descendant of the aunt or uncle, the tax paid was $3.00 per $100

inherited.

4. If the person was a great aunt or great uncle of the

deceased or the descendant of the great aunt or uncle. The tax paid was

$4.00 per $100 inherited.

5. For anyone not listed above, the tax paid was to be

$5.00 per $100 inherited.

6. If the deceased’s spouse inherited part or all of the

estate, no tax was to be paid on the portion the spouse inherited.

Taxes on Necessities

The War Revenue Act taxed those engaged in the production or packing of

“mixed flour” – defined basically as any flour that was not purely wheat

flour – at the rate of twelve dollars per year, plus between one and four

cents per barrel of flour, depending on barrel size.

Sugar refiners who had gross receipts of more than $250,000 were subject

to a tax of 0.25% on the gross sales.

The same requirements were put on oil refiners and on anyone “owning or

controlling any pipeline for transports oil or other products.” Again,

those companies that had gross receipts of more than $250,000 were subject

to a tax of 0.25% on the gross sales.

Again, the larger companies were taxed, and they could decide to pass that

amount along to customers or not.

War Bonds and Loans

The War Revenue Act allowed for the government to issue certificates –

bonds – that would bear an interest rate of three percent. The number of

bonds issued could not exceed $400,000,000 in total. It appears that

$198,792,660 in bonds were issued. The bonds matured on August 1, 1918. As

of October 31, 1918, $60,878,560 had yet to be redeemed. By October 31,

1919, that amount had decreased to $858,600.

In addition, the Secretary of the Treasury was permitted to borrow up to

$150,000,000 as needed.

The Aftermath

Some portions of the War Revenue Act had to be clarified and eventually

were taken to court, including the Supreme Courts. Some of the

issues included whether the revenue stamps requirements applied to certain

life insurance policies, patents, trademarks, and certain drugs. There

were issues on such diverse topics as the use of leaf tobacco, livestock

sales, etc.

The War Revenue Act was gradually repealed over the following four years.

On July 1, 1901, the revenue stamp requirements were repealed except for

certain specific sections. On July 1, 1902, the remainder of the War

Revenue Act was repealed, with the exception of the estate tax, which

remained.

In spite of what has often been stated, the tax on telephone calls was

repealed in 1902. In later years, it was reinstituted, but the more recent

taxes were not left over from the War Revenue Act of 1898, but from later

acts of taxation. The tax that did remain, in one form or another, was the

graduated estate tax.

Did the War Revenue Act do What it Was Intended to Do?

The goal of the act was to raise funds to pay off the debts incurred by

the war. A look at the annual deficit or surplus should indicate if the

debts were alleviated. In the fiscal year of 1897 to 1898, the country had

a deficit of $38,000,000, which rose to $89,000,000 in the 1898 – 1899

fiscal year. By 1899, the situation changed. In the 1899 – 1900 fiscal

year, the country ran a surplus of $79,000,000, followed in the 1900 –

1901 fiscal year by a surplus of $77,000,000. By the fiscal year of 1901 –

1902, the surplus had risen to $92,000,000.

The growing surpluses indicated that enough taxes had been raised to

offset the war-incurred debts. The surpluses caused a public outcry which

led to the repeal of the War Revenue Act.

Bibliography:Annual Report of the Secretary of the Treasury

on the State of Finances for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1918.

(Washington: Government Printing Office, 1919) 77.

Annual Report of the Secretary

of the Treasury on the State of Finances for the Fiscal Year Ended June

30, 1919. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1920) 113 –

114.

“Are Exempt,” Buffalo

Commercial. (Buffalo, NY), February 13, 1899, 10.

“In Supreme Court,” Chattanooga

Daily Times. October 13, 1899, 1.

Republican Text Book for the

Campaign of 1898, Published by the Authority of the Republican

Congressional Committee. (Philadelphia: Dunlap Printing Co.,

1898), 373 – 381.

“Taxes on Life Insurance,” The

Dispatch (Moline, IL). August 5, 1898, 8.

“Chap. 448 – An Act To Provide Ways and Means to Meet War Expenditures,

and Other Purposes,” The

Statutes at Large of the United States of America from March, 1897 to

March, 1899. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1898). 448

-470.

“Uncle Sam’s Balance Sheet,” The

Davenport

Times. (Davenport, IL), July 5, 1902, 6.

“Value of $1 from 1898 to 2020”

https://www.in2013dollars.com/us/inflation/1898?amount=1

“War Revenue Bill,” The Los

Angeles Times. April 28, 1898, 9.

“War Tax Soon to Go,” Sioux

City Journal. June 18, 1902, 3.

Support this Site by

Visiting the Website Store! (help us

defray costs!)

We are providing

the following service for our readers. If you are interested in

books, videos, CD's etc. related to the Spanish American War, simply

type in "Spanish American War" (or whatever you are interested in)

as the keyword and click on "go" to get a list of titles available

through Amazon.com.

Visit Main Page

for copyright data