This article discusses a "Trapdoor" rifle that is traceable to a particular soldier in the 22nd Kansas Volunteer Infantry

Given you have made the effort to access this website, and specifically this article, I’m sure you have an interest in the Spanish-American War and probably in the Kansas regiments that participated in that conflict. If so, you probably also have an interest in the arms and equipment used by those regiments. What you may not know is that, in some cases, Spanish-American War arms can be traced, through their serial numbers, to the individual soldiers who used those weapons. Unfortunately, these arms are pretty scarce, because such records were considered to be temporary in nature and only those that happened to be included in with more permanent records survive today. For example, roughly 600,000 Model 1873 and later Springfield “Trapdoor” long arms were made with serial numbers that would allow definitive association with servicemen, but only about 4.5% of those serial numbers have been found in government records. In addition, some of these documented guns have pretty limited histories. For example, the records for 50 of these serial numbers give only the dates the arms were manufactured, which is interesting and useful information but it’s not very exciting. As another example, the documentation for another 450 Trapdoors tell us little more than that the arms were in the Maine Militia in 1887-1889. That’s not a lot of detail but still, it is of interest, especially if you happen to be from Maine. On the other hand, some weapons are documented to historic events or famous people. Despite the often stark differences in their documented service histories, to me they all have interesting stories to tell, and the subject of this article is no exception.

Researchers have found only 1,005 Kansas serial numbers in regimental records at the National Archives. These serial numbers were found in the records of the 20th, 21st, 22nd and 23rd Kansas Volunteer Infantry records and they range from 77191 (made in approximately 1878) to 433253 (made in approximately 1889). The great majority of the serial numbers were under 300000. This tracks fairly well with issues to the State under the Militia Act as shown in the accompanying table and it is likely that all of the arms used by these regiments during the war were ones that had been issued to the State years earlier.

KANSAS .45-70 TRAPDOOR RIFLE ISSUES

UNDER THE MILITIA ACT 1

|

Date |

Description of Stores Issued |

Number |

|

8/20/1878 |

Springfield Rifles, Cal 45 |

320 |

|

7/19/1879 |

Springfield Rifles, Cal 45 |

109 |

|

3/19/1880 |

Springfield Rifles, Cal 45 |

149 |

|

8/3/1883 |

Springfield Rifles, Cal 45 |

400 |

|

8/27/1883 |

Springfield Rifles, Cal 45 |

50 |

|

8/20/1885 |

Springfield Rifles, Cal 45 |

500 |

|

8/13/1886 |

Springfield Rifles, M1884 |

340 |

|

6/18/1889 |

Springfield Rifles, M1884 |

160 |

|

10/12/1889 |

Springfield Rifles, M1884 |

200 |

|

Total |

|

2,228 |

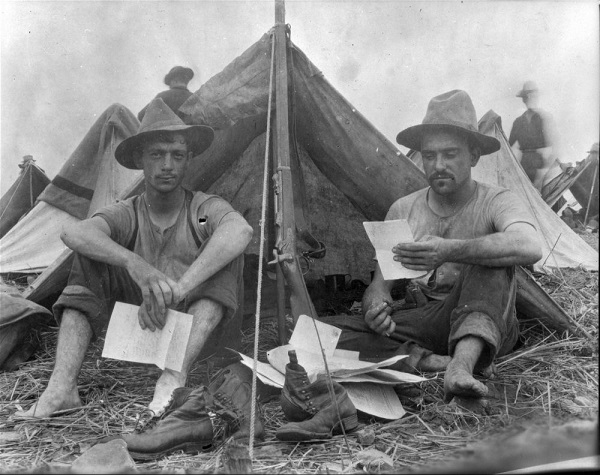

Only 94 serial numbers of 22nd Kansas rifles are documented; all were in “G” Company. They range in serial number from 184005 to 313347. One of those rifles, number 184062, which is illustrated here, was issued to Private Thornton L. Lewis. This rifle is a Model 1873 rifle that was manufactured in approximately 1882 and still retains its Model 1879 rear sight (some were upgraded to a Model 1884 sight). The barrel has considerable blue and the underside of the breech block has nice case coloring, although the exterior of the block and receiver are faded and speckled from age. Unfortunately the stock has been refinished, which removed most of the original markings.

Private Lewis was born in Granby, Missouri, and was a 21 years old blacksmith when he enrolled in the 22nd Kansas on 16 May 1898 in Topeka. At the time he was a resident of Galena, Kansas. His personnel record described him as being 5’ 10” tall with a fair complexion, blue eyes and brown hair. Given his occupation as a blacksmith, it is a little surprising that he was mustered into the regiment as a “musician (bugler). Lewis’ records shows little that is remarkable about his short service. In fact he was absent on furlough from 14 September to 13 October and then mustered out with the regiment on 3 November 1898. His medical record shows he was treated on 11 June for acute gastritis and on 12 July for tonsillitis and in both cases was returned to duty on the same day as his treatment. Like a great many Spanish-American War soldiers, he was also treated for dysentery on 22-23 June 1898. Obviously Private Lewis’ short but honorable service was not very significant but his service was not the reason I acquired this rifle. I bought it because of where it saw service, Camp Alger, Virginia, which was about four miles from my home.

In May 1898, the War Department established Camp Russell A. Alger2 on a farm of 1,400 acres called "Woodburn Manor" near a small community called Dunn Loring in northern Virginia. It was on both sides of the current Gallows Road in the area from current day Interstate 66 through Marrifield and down to the site of Fairfax Hospital (just south of Route 50 and just west of the Capital Beltway). In its brief existence, 23,000 men trained there for service in the Spanish–American War. Due to a typhoid fever epidemic, it was abandoned in August 1898, the month that the shooting war ended, and was sold the following month. The camp is commemorated by an official Virginia historical marker, which is on Route 50/Arlington Boulevard just inside Washington’s Interstate 495 beltway and near Falls Church High School.

The 22nd Kansas left Topeka for Virginia on 25 May 1898 and three days later arrived at the Dunn Loring railroad station and then marched to Camp Alger. Their service there is well described on the excellent Kansas National Guard website3, which includes a regimental history that, in part, is based on the diary of one of the regiment’s members, Pvt. Samuel Adams of Topeka. Much of the history included here is from that website.

The daily duties of the men included drill, sham battles and guard duty. The boring duty, the hot Virginia summer, poor food, infrequent pay, and the disappointment of not seeing action in the war all contributed to poor morale and slack discipline within the regiment. Drinking apparently became such a problem that patrols were sent out to discourage moonshiners and bootleggers. Even the acting regimental Sergeant Major, George A. Elliott, was arrested for getting drunk and threatening an old man who lived nearby with a revolver and ransacking his house. The behavior of the troops was such that every 24 hours 75 men were detailed for sentry duty around camp to keep the Kansans in rather than to keep strangers out.

In July a typhoid epidemic hit Camp Alger and 15 men of the 22nd died from the disease. Army authorities decided to remove some of the troops to healthier camps, and on 2 August 1898 the regiment began a march to its new camp near Manasas, Virginia, less than twenty-five miles away. It did not reach its destination until a week later and along the way its lack of discipline was sorely evident. Pvt. Adams wrote in his diary: “The boys have gotten tired of their slim diet of hard tack, potatoes, onions, “sow bosom” and coffee and are scouring the country for everything they can find. They are almost all broke, and so take apples and chickens and despoil the milk houses of milk and butter. It is reported to-night that they did not stop with smaller damaging. But killed beefs, robbed graves for relics and molested the inhabitants.” The most infamous charge of grave robbing was made against Capt. L.

C. Duncan, the 22nd Kansas Volunteer regiment's assistant surgeon. He

was charged with desecrating the graves of two Civil War Confederate

soldiers. Virginia citizens were enraged. A General court-martial was

soon convened with the trial lasting 14 days. Duncan was found not

guilty of the grave robbing charges but guilty of "conduct prejudicial

to good order and discipline'' in failing to arrest enlisted men who had

committed the crime. He was sentenced to loss of rank for two months,

the forfeit of half his pay for the same period, and to be confined to

the regimental camp but the sentence was set aside by the convening

authority.4

Notes:

1. National Archives, Record Group 156, Entry 118.

Kansas received only two .50 caliber rifles (Model 1870 rifles issued

in 1874) and two .45-70 carbines (issued in 1880). The State also

received two “Springfield Sporting Rifles” in 1875. The State still

had their Trapdoor rifles in 1900 for they had 336 rifles repaired by

Springfield Armory in that year at a cost of $349.54.

2. Russell A. Alger entered the Civil War as a private and rose to the

rank of colonel, and to the command of the 5th Michigan Cavalry. He

was given brevet promotions to brigadier and major general after the

war. After the war he was successful in both business (especially real

estate and lumber) and politics (he served as Michigan governor and

was considered for nomination to run for the presidency under the

Republican ticket). Appointed Secretary of War by President McKinley

in March 1897, Secretary Alger was blamed for many of the problems

that had plagued mobilization for the war and the Army’s execution of

it. He resigned at the President’s request but was mostly exonerated

after investigation by a presidentially-appointed commission. However,

his reputation was never fully recovered.

3. http://www.kansasguardmuseum.org/dispunit.php?id=31

4. Following his court-martial Duncan was arrested by the sheriff of

Fairfax County, Virginia, handcuffed, and confined in the county jail

until he could make bail of $1,100. But according to one source the

sentence eventually given to him was only a $100.00 fine.

http://www.kansasguardmuseum.org/dispunit.php?id=31