The "Living History Crew of the USFS OLYMPIA" loses one of its own:

In Memory of

Michael Borsuk

(September, 1954 - June, 2000)

(September, 1954 - June, 2000)

On June 29, 2000, the Living History Crew of the OLYMPIA lost one of it own. On that date, Michael Borsuk passed away at the Temple University Hospital after a long battle with a terminal liver disorder. He had been on the transplant list for two years, but the needed transplant did not come through in time.

Mike was a registered landscape architect and a professional model builder having his own firm called “Site Specific.” Mike’s ability, creativity, and attention to detail was a credit to his profession. He was a graduate of the University of Idaho, and also held an associate’s degree in engineering from Temple University. In over ten years of my having worked with Mike periodically on a professional basis, I can truthfully say that no one I knew ever detected an error in Mike’s work, a truly remarkable achievement and a testament to Mike’s thoroughness. Mike’s models of buildings and other projects were remarkably detailed and true works of art. His designs showed true innovation and thought, not mere “code book minimum,” as well as a true understanding of how people related to their environment. However, in spite of Mike’s ability, history will show that this is not his legacy.

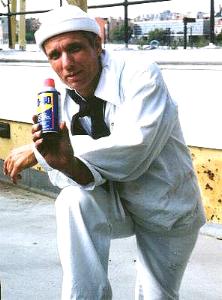

Mike applied his professionalism to his

activities aboard OLYMPIA as one of the

original members of the Living History Crew of the

OLYMPIA. The crew had no more important asset. Mike was thrilled

to do whatever he could aboard ship, giving tours, running up signals,

acting as the plugman on the guncrew, singing chanties….whatever was

needed. Mike was always the first up in the morning, running out to

get supplies, or preparing breakfast for the entire crew (not just

donuts…but breakfast to order, from eggs, to pancakes to fruit

cocktail, to bagels, etc.). Mike taught himself to use the

‘bo’suns pipe” just for fun. When our usual ship’s

chaplain could not be present, Mike gladly stepped into the role and

filled it masterfully, with his sincere faith shining through. Being

the only crewman actually from the Philadelphia area, in the hours

after the ship closed, Mike guided his fellow crewmen to places where

they could get whatever supplies they needed, or simply a good place

for dinner. History will show that, in spite of all he had done for

the OLYMPIA, this is not his legacy.

Mike’s legacy is much simpler. It is not based on his many achievements, his work aboard OLYMPIA, or his even more extensive work in railroad history and preservation. Mike’s legacy is that he was a kind, gentle person, with a fun-loving but thoroughly religious soul, whose word could be trusted more than a written contract. In reality, no one can remember Mike having a nasty word to say about anyone. If only slightly prodded, he would burst out in song, usually with old Polish songs which he would teach others to sing so they could join in. Mike could also do a great (and loud) impression of Ricky Ricardo which always put anyone around him into roars of laughter. Mike spread joy, happiness, his zest for life, and energy to anyone he came in contact with. This is Mike’s legacy. Planning for land use, buildings, monuments (even OLYMPIA) are all fleeting items. The best we can do is, with great care and expense, keep them around a little longer. Mike’s legacy and personality affected many people over several generations. This affect, though not obvious, pompous, or showy, will continue beyond our lifetimes and our monuments.

Mike had fought his liver ailment for years, knowing it was considered terminal. He resisted getting himself on the transplant list stating that there were others out there who needed a transplant more than he. In time, the disease took its toll. At one event aboard OLYMPIA, Mike told us that he was finding himself having more trouble moving around, and his pain climbing the ladders, etc. was showing. The disease had contributed to the weakening of his bones, and he later found that he had several cracked vertebra. He was forced to use a walker and had to shut down his office. Still Mike looked at his illness as a temporary problem, talking about his plans “when he got to the other side” of it.

The last time many of us saw Mike at the ship was in April of this year (2000). He and his father came out to deliver water to us. More than the water (a precious shipboard commodity), we were happy to see him. He was now much more frail, complexion was badly altered, and he was moving slowly. Still, the personality shone through. He smiled, joked, used his walker to race his father who was pushing a handtruck, and delighted in the noise he could make by pushing his walker across the aluminum gangplank. Mike showed little of the disappointment he must have felt. A transplant match had been found, but because of the damage caused by some of his medications, he was temporarily not healthy enough to receive the transplant when it had been available shortly before.

Mike worsened. He spent nearly a month in intensive care. We visited, and through the cloud of pain, pain killers, respirator, tubes, and wires, Mike was only able to acknowledge our presence with a slight nod of the head and a movement of the eyes, something that must have required incredible energy. He seemed to want to tell us more, but he could not. We understood.

Life followed its continuous step onward, and Mike passed from our presence into another which he often stated that he was prepared for. Several of the crewman had the honor of being among his pallbearers.

Today Mike lies in Forest Lawn cemetery, near a locust tree. But he is not really there. He’s in our hearts and minds where he will be alive always.