Feeding the U.S. Navy

By Patrick McSherry

Please Visit our Home

Page to learn more about the Spanish American War

Click

here for recipes for Navy food of the Spanish American War

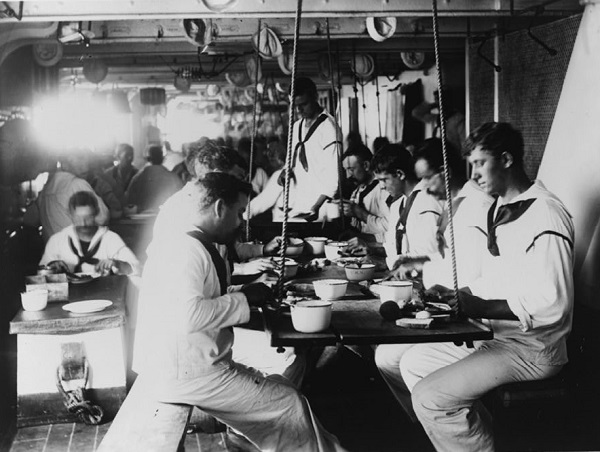

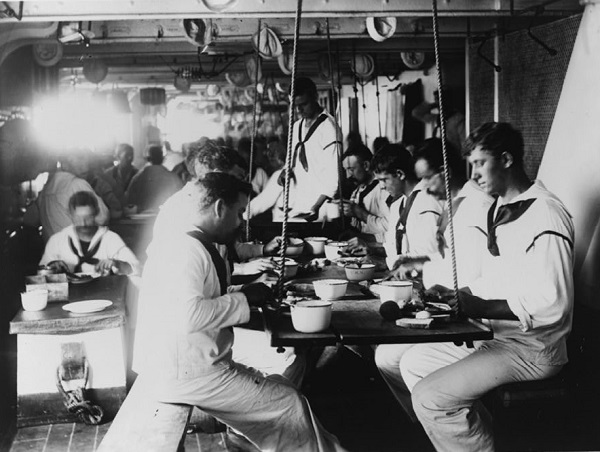

A

mess on the OLYMPIA sits down for a meal. Note the ropes supporting

the table, and

the man at left dining off a trunk of some sort. The men have hung

their hats on the hooks that

will later be used to support their hammocks (Photo: Library of

Congress)

General:

This article will address how the crews of the ships of the U.S. Navy were

fed.

The article:

Most people assume that the naval crews of the Spanish American War period

were simply provided with food by the U.S. government and that this food

was prepared by a cadre of professional navy cooks. This was not true in

the Spanish American War period or before. However, after the Spanish

American War, the system was changed and modernized.

Feeding the Enlisted Men:

During the Spanish American War, ships’ crews were divided into “messes”

of about twenty men each. The Navy allotted thirty cents per day to

feed each man. A certain portion of that money, usually twenty-five per

cent, was paid cash to each mess, with the remainder carried on the books

of the mess. Each mess appointed a treasurer or “caterer” whose job it was

to handle the money. The funds carried on the books were used to purchase

basic supplies from the paymaster’s storerooms – salt beef or salt pork,

potatoes, onions, etc. The cash was used to purchase supplemental items

while in port from stores or from “bum boats” – boats which would come out

to the ship and offer things for sale to the crewmen, such as fresh

produce, eggs, various spices or condiments.

If a mess had a good “caterer,” the funds would be used wisely to

supplement the somewhat boring – and sometimes unappetizing - shipboard

fare. If the caterer was not wise, the money could be spent too rapidly,

and would not last until the next allotment of funds was made available

the next month. This could simply result in the mess having to eat only

the more monotonous supplies available from the storeroom, or in worse

cases, the mess may not even have the fund to purchase from the storeroom.

In this case the mess was fed on coffee and hardtack until funds were

again available. On occasion, crews would not choose well, and man

selected as caterer had an affinity for alcohol, Such a person may spend

the cash portion of the mess’ monetary allotment on whiskey from a bum

boat…

The food supplies purchased from the paymaster’s storerooms or while in

port would have to be prepared. Again, this was the responsibility of the

mess. The mess would appoint a cook, known as a “berth deck slusher,” who

would be required to cook the meals in the ship’s kitchen, known as the

galley, under the watchful eyes of a navy cook. The navy cook did not

prepare a menu, as the supplies from each mess would vary. The quality of

the food depended on the capabilities of the berth deck slusher. Most men

did not enter the service with experience cooking for twenty people, so

there was usually a learning curve. Unlike the army, the navy had not

created a cookbook for the use of the cooks. That would not happen until

1902, when the navy went to a mess system where the mess was not managed

by its members, and a staff of cooks and bakers were provided.

Many of the recipes were simply handed down by word of mouth or

demonstration and were given interesting names such as “Plum

duff,” “lob dominion,” “lobscouse,” "sea pie," “skillagallee,” "slumgullion,"

and “burgoo,” etc. Plum

duff

was traditional aboard ships of many nations, including the U.S. and

Great Britain. The “duff” in the name supposedly came from a

mispronunciation of “dough.” “Dough” is spelled like “rough” and must

pronounced the same, hence “duff.”

At times the messes had unique opportunities to supplement their larders.

In one case a naval vessel encountered a schooner hauling watermelons. The

ship stopped to allow the messes to purchase watermelons, and large

quantities were purchased. The same naval vessel encountered a fishing

boat and the messes purchased almost the entire catch. During the war,

Spanish ships hauling cattle or pigs were captured and their cargo

supplemented the ship’s larder with fresh meat, a welcome switch.

As a point of reference on the sheer amount of food supplies that a navy

vessel would require, the following is a list of foodstuffs consumed

aboard from the Armored Cruiser Brooklyn to feed its 470 enlisted crewmen

for one month. The list does not include supplies purchased independently

by the various messes:

“This crew in one month consumed 6,000 pounds of bread, 35 pounds of

yeast, 3,000 pounds of sugar, 300 pints of condensed milk, 600 pounds of

coffee, and 100 pounds of tea, I,000 pounds of butter, 200 pounds of lard,

8,000 pounds of fresh beef, 2,000 pounds of fresh fish, I,800 pounds of

salt pork, I,200 pounds of salt beef, 800 pounds of liver, 6oo pounds of

ham, 480 pounds of bacon, 600 pounds of pork chops, 300 pounds of

sausages, 400 pounds of salt mackerel, 500 pigs' feet, 800 pounds of

tinned meats, 240 pounds of bologna, 240 pounds of cheese, 800 pounds of

rice, 300 pounds of macaroni, 300 gallons of beans, 400 bushels of

potatoes, 12 bushels of onions, 20 bushels of turnips, 600 heads of

cabbage, I20 quarts of clams, 480 quarts of catsup, 12 pints of flavors,

I00 pounds of dried fruit, 300 pounds of salt, 30 pounds of pepper, 24

pounds of curry powder, 300 pounds of pickles, 3o gallons of vinegar, 30

gallons of syrup, and to make one omelette for the immense crew for one

morning's breakfast, I,500 eggs.”

The tables were stored on racks or by ropes over head on the berth deck. When meals were rady to be served, the tables

were lowered. After the meals, the tables were replaced in the racks or

raised back up. At night, the crews' hammocks were slung from hooks on the

overhead. It has been said that the men ate under where they slept and

slept under where they ate.

Feeding the Officers:

For officers the situation was quite different. The government did not

purchase food for the officers. That was the officer’s personal cost and

responsibility. Officers would contract with a catering company, some of

which had worldwide operations. These companies would provide food

directly to the ship and to the officers’ mess. There were stewards whose

job was to prepare and serve the food.

The different systems for the officers and enlisted men created some

friction. The enlisted men would see their limited options or suffer a bit

in a period where supplies would run low. When this happened, they may

note that the officers were still living quite well, making the enlisted

men indignant. Often the enlisted men did not understand that the officers

had to provide their own food, which would still be delivered even if the

government-supplied basics did not. Alternatively, if an officer was

well-liked or respected by the crew, should the officer’s food run low, a

mess may decide to provide some of their larder with him. If an officer

was not well-liked, times of want could be difficult.

Bibliography:

Alden, Cmdr. John D., USN (Ret.), American

Steel

Navy , (Annapolis: United States Naval Institute Press,

1972), 277, 289.

Brady, Cyrus Townsend, Under Tops'ls and Tents. (New York:

Charles Scribner's Sons, 1901) 122-123.

Graham, George Edward, Schley and Santiago. (Chicago: W. B.

Conkey Co., 1902), 62-63, 67-68.

Young, Louis Stanley, The Cruise of the U. S. Flagship OLYMPIA.

(Cruise Book), 85.

Support this

Site by Visiting the Website Store! (help

us defray costs!)

We are providing

the following service for our readers. If you are interested in

books, videos, CD's etc. related to the Spanish American War, simply

type in "Spanish American War" (or whatever you are interested

in) as the keyword and click on "go" to get a list of titles

available through Amazon.com.

Visit Main Page

for copyright data