Why was the Spanish American War fought? What was the cause of the Spanish American War? There were six main reasons for the war: The U.S.' need for coaling stations, the ongoing war in Cuba, the effort to draw the U.S. into the Cuban conflict, the romanticizing of the Civil War, an ongoing belief in Manifest Destiny and the fading power of Spain. Some will say it was because the Battleship Maine exploded in Havana harbor, but that is a far from complete answer.

Six Reasons Why the War Was Fought

First, it is important to keep in mind that

virtually all wars are fought for one of two reasons – religion

or access to resources. In the case of Spanish American War, access to

a resource was a major factor. That resource was coal. The

United States had been an isolationist nation, and still was in the

years leading up to the Spanish American War. Economically,

isolationism worked as the nation had the ability to expand

economically within its own borders or within limited distances from

its coasts. As the nineteenth century was reaching its closure many in

the United States realized that to continue the expansion, the country

had to expand overseas economically.

Overseas economic expansion had certain requirements. One was a commercial fleet. The United States did not have a commercial fleet, for one main reason. What kept commercial vessels from falling prey to foreign forces in ways ranging from piracy to harassment in certain markets was a navy that could defend their interests. Without a navy to back them up, shipping companies were unwilling to have their ships flagged as American vessels. To have a worldwide commercial fleet required a worldwide navy – or a navy that could travel anywhere in the world to defend its commerce. The government had the foresight to begin to provide the naval vessels with this capability – the country’s first true battleships, the Indiana Class battleships: U.S.S. Indiana, U.S.S. Massachusetts and the U.S.S Oregon. To satisfy the isolationists in congress, these ships had to be called “Seagoing Coast Line Battleships,” to indicate that they were to be defensive instead of offensive weapons, but they had the coal capacity to cross an ocean. The capability to truly defend a commercial fleet anywhere around the world was dependent on one thing - access to coal. Every ship's range was limited by how much coal it could carry to fire its engines. Without coal, the ship could not move. Coal could purchased from other nations when the ship was cruising far from the U.S. coast. However, in times of war, access of the nation’s warships to foreign coal could be denied by other nations under neutrality laws. To be a true worldwide navy, the United States had to have coaling stations around the world that were under its undisputed control and where warships could recoal without having to retire to the United States itself in times of war.

Earlier in the 1890’s the U.S. Navy studied where coaling stations would be needed based on ship cruising ranges, and suggested places such as the Philippines, Guam, and Puerto Rico, among others. Many of these areas were part of Spain’s colonial empire. The navy developed battle plans in case war with Spain would occur to secure these resources. By the time of the Spanish American War, these plans had existed for several years.

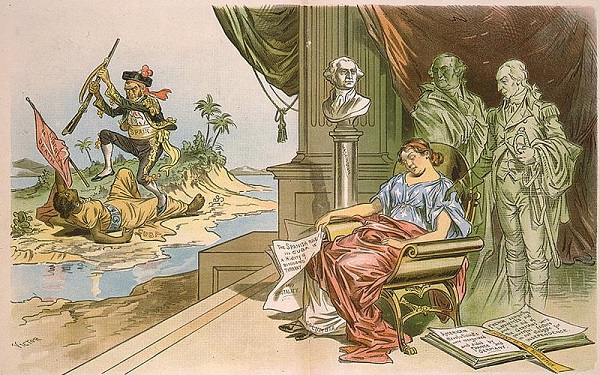

A second major factor were the conditions in Cuba and the treatment of its citizens going back twenty years or more. Starting with Cuban Ten Years War and the Virginius affair and up through the beginning of the Cuban Revolution and the Reconcentration Policy under Governor General Weyler, conditions in Cuba were often brought to the attention of the American public. Actions against Cuban civilians – real, exaggerated and false - received coverage in the American “Yellow Press.” These reports mainly impacted public opinion in urban centers where the Yellow Press was most prevalent with some trickle-down impact on the remainder of the rural nation. When the Cuban Revolution broke out in 1895, many Americans took the side of the Cuban underdogs against Spain, to the extent that an arms trade developed with arms being shipped by private entities (not the U.S. government) to the Cuban forces. Cuban leaders such as Jose Marti and Tomas Palma came to the U.S. and promoted the cause of “Cuba Libre.“ These conditions, combined with the country’s policies related to the Monroe Doctrine, kept the issue of Spanish control of the island in the nation’s mindset for many years.

Third, there were efforts on the side of the

Cubans to draw the Americans into the conflict on the side of the

Cuban revolutionaries, a stated goal of Cuban leader Maximo Gomez.

There was substantial American private investment in the island’s

sugar industry. American plantations were damaged or destroyed by

Cuban forces with the belief that the American government would be

prodded by wealthy and influential plantation owners to react to stem

the losses. Cuban leaders knew that if the U.S. government acted, in

view of the press coverage of the plight of the Cuban population, it

would enter the fray on the side of the Cubans, not Spain.

Fourth, there was the issue of the aftermath of the American Civil War. The war was brutal, and horrible as are all wars. The Civil War, however, directly impacted almost every family in the country. The men who served in the war formed strong bonds with the men that they served with. The bonds formed under fire were often as strong as family bonds. In the ensuing years, the veterans formed organizations with their comrades, often promoting the glorious actions of their regiments and regaling in their comradeship. As with most horrible events, the horror has a tendency to fade, but the glorious actions and the comradeship remained. As the Spanish American War approached thirty years later, a new generation had grown up in the stories of the glorious actions of their fathers. To them war was less a horror, and more of an opportunity to share in the glory and comradeship experienced by their fathers. The truth of this became apparent when the Spanish American War broke out and the call went out for volunteers. More volunteers were received than were needed. It got to the point that the federal government refused to accept additional volunteer regiments from the states, so the states responded by enlarging the already accepted regiments from nine to twelve companies, adding about three hundred unwanted men to each regiment! Competition to get a position in even the expanded regiments was so strong that very, very few underage soldiers were accepted, contrary to many family legends. As companies raised were local, underage men were usually “ratted out” by those who knew them and removed from the company to allow for someone who met the qualifications to join.

Fifth, there was the issue of Manifest Destiny lingering in the U.S. as it had for the previous fifty years. This belief was that the U.S. was endowed by Divine Providence with a mission to bring its forms of government and religious beliefs to other peoples to improve their lives, or, in some cases, to “bring them civilization.” This belief meant that some felt it was the duty of the U.S. to bring its beliefs to other, less developed nations.

Sixth, Spain was a declining power. Its armed forces, though well-led and as brave as any other, were not keeping up with other nations. Many naval vessels had been designed to maintain it colonies, not to go head-to-head with modern navies other nations. Spain had severe economic issues, and funding for its armed forces was significantly decreased. In fact, live-fire practice was seldom done for cost reasons, and with this lack of target practice, the ability of its military to perform in war was significantly decreased. Though many still considered Spain to be a strong world power, and expected the U.S. to lose the conflict, those in power knew the true conditions.

Entering into all of the this was the sudden

explosion of the Battleship Maine in Havana

harbor. This brought the voices of everyone promoting beliefs

mentioned above to a fever pitch. The 1898

"Sampson Board" investigation into the loss of the Maine

indicated that it was lost to a mine that triggered the greater

explosion of an ammunition magazine, dooming the ship. It is

noteworthy that the investigation did not fix blame on who was

responsible for planting the mine. Instead the emphasis was on Spain's

failure

under international law to protect the foreign vessel in its port

from destruction. It is also noteworthy that the U.S. has never

changed its official view that the ship was sunk by a mine, and the

U.S. never accused Spain of planting a mine. A second official inquiry

was held in 1911 ("Vreeland Board") and reached the same conclusion. A

third private (unofficial) study ("Rickover") was done in the 1970’s

blaming the blast on a coal bunker fire,

but the evidence for this conclusion is lacking.

Many in power saw the opportunities presented by

the situation in Cuba on the aftermath of the loss of the Maine.

Those pushing for any or all of the reasons above pressed for war. The

U.S. mulled the idea over. Though the Maine was

sunk on February 15, the U.S. did not declare war until April 25, over

two month later. The declaration of war

did not mention the Maine, as that was not truly the issue, but focused on the

independence of the Cuban people. The conditions and forces listed

above led to the removal of Spanish control from Cuba,

and other locations around the world.