By E. Taylor Owens

To read about the 2nd Texas,

Co. K Re-enactment organization, of which the author is a member,

click here

Click

here for a partial roster of the 2nd Texas Volunteer

Infantry, Co E

To read the obituary of one of

the unit's members, George Sparks, click here

This unit was raised in Dallas, Texas during the Spanish American War. The unit had the experience that was common to most of the American Volunteer units of the period, which was to languish in a stateside camp, fighting the enemies of disease and boredom. They never had the chance to face their foe on the battlefield, an experience which embittered some men, and made others very thankful. This is their story as told through Mr. Owen's research and his unique point of view.

The Unit History:

I am a re-enactor. There! I said it, and Iím glad! It's nothing to ashamed of. It happens in the best of families. I make this confession only because it was while trying to find a Spanish American War unit to re-enact that I stumbled across Dallasí first Boys of Summer, the summer of 1898, Company K, The Dallas Guard Zouaves.

I am getting ahead of myself. I should first remind you that 1998 was the centennial of America's war with Spain. I don't blame you if you don't know much about that ugly little war. It is hardly mentioned in history classes any more. There may be some passing reference to Teddy Roosevelt (who ever he was) charging up some hill somewhere in (Mexico?), but that's about all. So why would anybody want to re-enact this? Unless you are a reenactor, it is hard to explain. Let us just say that Civil War re-enacting has been done.

My goal was to find an authentic local unit to represent. A check of the Dallas historical and heritage societies provided some information. The Dallas Morning News' microfilm collection produced a little more. Finally, with the help of the Texas State Archives in Austin, a story began to unfold: not just a story of some obscure infantry company, but a picture of the summer of 1898. Of a time when Dallas bragged of having the only cable car south of St. Louis and that most of her streets were lighted by electricity, a very familiar picture of growth, prosperity, and of being more than just a little arrogant. I began to feel very comfortable with that summer a hundred years ago.

It was the custom in the late nineteenth century for any self-respecting town to have at least one militia. The Bull of the Trinity, as folks liked to call Dallas, had several. They were little more than heavily armed social clubs, comprising the sons of the city's elite. They wore gaudy uniforms, paraded on the Fourth of July, and on one occasion, the Dallas Light Artillery, broke up a railroad strike in Fort Worth, but they were never meant to go to war. Dallas even had an all Black militia, but unfortunately I can find no more information about it other than it did exist. Maybe it was hoped the history of Black Dallas troops would be buried under Central Expressway with Freedman's cemetery.

Be that as it may, when the USS Maine blew up in Havana Harbor on February 15th, 1898, these small town militias began stepping all over each other for the privilege of going to war. REMEMBER THE MAINE AND TO HELL WITH SPAIN! and °CUBA LIBRE! (free Cuba!) could be heard at every street corner from New York to San Francisco. News papers and politicians made much hay by fanning the flames of war. By April, famous Civil War militias, including the Dallas Light Artillery, found themselves competing for headlines with such Johnny-come-latelies as the Dallas Guard Zouaves and the Trezevant rifles.

Cowboys, ploughboys, and schoolboys from all over North Texas poured into Dallas, trying to join one of the newly formed Texas volunteer regiments, to go with heroes like Colonel Louis M. Openheimer, to take liberty, justice and the American way to Cuba, and to free the oppressed people of the Philippines. Yeah, right! In reality, it looked like a lot of fun to a bunch of bored North Texas kids. And at $13 a month, who could resist? It had been so long since America had fought a real war that we had forgotten just what that meant. As one old wag said, "Two months ago the typical American didn't know if the Philippines was an island or canned goods, but now they're ready to go to war over the place."

As the 2nd Texas Volunteer Regiment grew, the city was compelled to find food and lodging for it. Soldiers were housed all over downtown. The Dallas Zouaves were quartered in stores near the southwest corner of Elm and Hawkins. Some of the buildings still remain, and need protecting. The barracks of the Trezevant rifles was situated at the corner of Main and Harwood. Newspaper reports of the day tell how the good folks of Dallas enjoyed watching the regiment drill in the streets of downtown.

The old West Dallas brickyard was turned into a cavalry parade ground for a time. It was here that cavalry Troop C, of the 1st Texas Volunteer regiment trained. If you got bored watching the infantry do bayonet drill, you could just hop over to the west side and watch a practice saber charge. Now that's entertainment.

Dallasites could not do enough for their soldier boys. Stores offered discounts to soldiers. The MK&T Railroad assured any of its employees, who might wish to leave and join the army or navy, that they would find their jobs waiting for them upon honorable discharge. Groups of patriotic young ladies visited the various companies and helped keep moral high by singing popular songs. No one could say that Dallas didnít know how to treat its brave, young soldiers. There was only one problem: The regiment had no money.

By May there were hundreds of young, bored, and unemployed men hanging around downtown and folks were beginning to wonder just when they were going to leave. After all, patriotism is a good thing, but it doesn't jingle in the pocket.

Finally orders came from headquarters to move the troops to Camp Mabry near Austin. To get the regiment on its way a special train was put together. It is hard to say whether or not the town was glad to see them go, but the paper talks about how quickly the train was put together. This began what may have been the most uncolorful military campaign Texas has ever seen. And I am proud to say that it began in my hometown.

Just before Troop C left for the war, the ladies of Dallas presented them with a proper Texas flag to carry into battle. Remember, in those days we were Texans first and Americans second. I wonder what happened to that flag? It is not the kind of thing one would lose.

Their stay in Austin was short, just long enough to be issued ill-fitting clothing and obsolete weapons. Not being national troops, they were issued the old single-shot 45/70 rifles, a deadly accurate weapon, but which puffed out a cloud of smoke roughly the size of a cow. They were told that this was a good thing because they could hide behind the smoke. I don't see how that would have been much help rushing Spanish machine guns.

Their time at Camp Mabry was also spent waiting for other units to

arrive and flesh out the regiments. They came from all over the state.

Groups like the Fort Worth Fencibles and the Mexia Minute Men. All with

the same boyish innocence as to what they were about it get into. But on

May 13, 1898 the regiments were sworn into the serve of the United

States of America.

On May 20th the regiments were put onto another special train (there's that word again) and was sent to Florida, which was to be the jumping off point to Cuba, Puerto Rico, and any place the war might take them. Unfortunately, by the time the soldiers got to Miami, the government felt that it had sent enough troops to the war. Our noble lads spend several weeks camped out in a swamp, fighting mosquitoes. One Dallas soldier described Florida as "the foulest place on earth." Of course this was long before Walt Disney World.

In July they were moved north to Jacksonville, which was only marginally better. They were grouped with other state troops (who were also not going to war) at a place called Camp Cuba Libre. What the regiment had missed in Spanish bullets was made up for with yellow jack (yellow fever), malaria, and dysentery. It was here that the regiment sustained its casualties. Clarence Riley died of chloroform poising during surgery, and George Proctor died of dysentery.

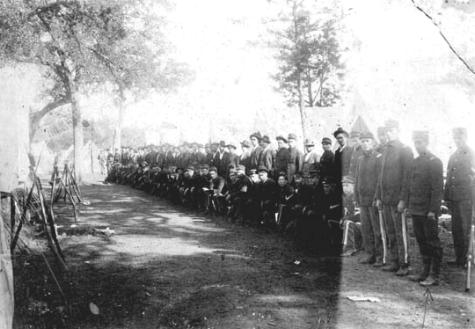

Camp Cuba Libre must not have been all bad. I have seen a few photographs from the place. One is of a group men holding a small spotted pig. I have no idea what was meant by that, but everyone seemed to be happy.

Besides spotted pigs, the 2nd Texas Regiment also picked up a small boy named Roy Nokes, age 11. As the story goes, Roy, was a runaway from Nashville, Tennessee. He wandered up to the camp one day and so charmed the Texans that they made him their mascot. A small size uniform was purchased for the lad and he quickly became the most visible man in the outfit. And when orders came for the troops to return to Dallas in late September, Roy came along with them. I can only imagine what became of the spotted pig. [see Editor's note, below]

To keep this story honest, I need to tell of one unpleasant incident. When the regiment was about to leave Camp Cuba Libre, the army sent over a black paymaster. The mostly white (there were a few Hispanics) regiment refused to the be paid by a Negro, and threatened to mutiny. Major Beaumont B. Buck, commander of the 2nd Battalion, a highly respected officer, told the troops that this was the way things were done in the army, and any man who did not comply would be dishonorably discharged and not paid. This settled things down, and the boys came home. It would be easy to look back now and talk of racism, but you should never judge the people of one time by the standards of another. There's a whole other story.

On September 23rd the first of three special trains arrived from Florida. With it came the regiment's equipment and a number of soldiers who needed medical attention. The soldiers were loaded into ambulances and taken to Parkland Hospital where they recovered. For a time the good 'ol Morning News printed daily medical updates on each solider and the town seemed genuinely concerned.

A temporary camp was set up at the end of Elm Street just east of what is now the bus barns for DART. Camp W. L. Cabell, as it was named, was nothing but an empty cow pasture filled with white tents, but for a while it was the place to see and be seen. These were no longer rosy-cheeked boys, but tough, browned-by-the-Florida-sun soldiers. There was more than a little resentment from the town boys who had stayed behind. The ladies of Dallas much preferred the handsome young soldiers. The closest thing I can compare it to, might be final review at College Station. Little Roy Nokes stole everyone's heart, and when one reporter asked what his future plans were he said, "A friend is going to take me back to Memphis just as soon the regiment was mustered out."

There was a rumors in the camp that we might be going to war with Germany in the not to distance future. Germany also had its eye on the Philippines, which was now American territory. "If there's going to be a fight with Germany we don't need to be mustered out." Said some soldiers, "We're just as eager to fight for the country now as we were the day we enlisted. We can stand any hardship if they will just let us fight."

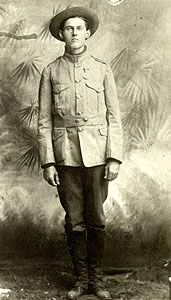

It quickly became "the thing" for the townsfolk to turn out every afternoon at 5:30 to watch Sergeant Major Tom Connally strut the regiment. This was what they called changing the guard. Tom was said to be the handsomest man in the regiment. Standing 6-foot- 2, in his dark blue uniform, he epitomized the American soldier. I do not know if the comparison is good or not, but a few years ago I watched the Dallas Cowboys parade up Young Street after a Super Bowl win. I will bet the enthusiasm was just about the same.

All this military pomp and circumstance was something new in Dallas streets. If you can believe the news paper reports, a sense of pride settled over Dallas. The employees of Padgitt Brothers headed by their Forman, made up a purse and taking it to the mother of Sergeant Birdsong F. Baldwin, on South Harwood Street. said, "Madame, we desire you to get Bird all the good things the stomach of a Texas volunteer can crave, and fill him plumb up, as a slight token of the appreciation felt for him by his fellow employees".

After a couple of weeks of welcome-home banquets and parades up Elm Street, the regiment was furloughed until the first of November. Some of the troops had not had enough army life so they joined the 23rd U.S. Infantry (regular army) and went to the fighting in the Philippines. There is not much information about what the rest of the regiment did for the next few weeks, but when they returned to Camp Cabell, things had changed. Many of the once happy soldiers were now poor and in rags. Much of the regiment seemed all but destitute.

Mustering Out Day was on November 9, 1898. It was a cold, blustery day, and many of the men were wrapped only in blankets. Men in worn-out shoes stood shivering in long lines, quietly wanting for their back pay. When the pay wagon finally arrived, it was escorted by Lieut. O. R. Brooks and a detail of men from the Dallas Zouaves, and three cheers went up. Over $129,000 was paid out that day, with each man receiving between fifty and one hundred dollars. There had never been that much money dumped into the Dallas economy at any one time. And the city took full advantage of this windfall. One Dallas department store said it sold three hundred suits that day.

A reporter for The Dallas Morning News who was at the camp that day said he saw a barefoot boy wrapped only in an old quilt shivering from the cold. His face was red and chapped form the harsh wind. The boy was crying inconsolably. The reporter did not say what the boy's name was, but only that he was the regimental mascot. Roy Nokes? The story goes on to say that as one soldier came out of the paymaster's tent, he looked at the boy then peeled off a couple of greenbacks and handed them to him saying gruffly as if to hide his feelings, "Here kid, take this and go buy some shoes."

There were a lot of sad scenes around town that day, including men still sick with malaria being helped onto trains for the long ride home. Everywhere men were singing "There's No Place Like Home," and saying good-bye to the best friends they had ever had. I guess to some of us one hundred and one years on it might seems a little hooky, but these men never expected to see their friends again. There is a special bond that grows between men in uniform. If you have never been in the military I can not explain it, and if you have I do not need to.

And that was that. Colonel Openheimer dismissed the regiment and returned to his plantation in Montague Co. One Dallas man who had gone to the fighting in the Philippines was decorated for his bravery in the battle for Manila. Apparently he planted a flag on top of a block house or something, and almost got himself killed in the process. Sergeant Tom Connally became one of Texas' longest sitting congressmen. In 1928 he defeated Senator Earle B. Mayfield, a Klansman. Connally urged voters to "turn out the bedsheet-and-mask candidate." I don't know what became of Little Roy Nokes, but it sounds as if he was a tough kid, so I like to think he made it back to Tennessee and became a great man, but there's no way to know.

[Editor's note: the author forwarded some additional info. on Roy Nokes that he received from Larry N. Pumphrey of Los Angeles, CA. Nokes was apparently 13 years old, rather than 11. By 1910, Roy was living in Tacoma, Washington and was employed as a sign painter, his life-long career. He married in. Three months later, Roy married Sophie Olsen in Coos Co., Oregon. 1920 found he and Sphie in Fresno, California, where he died on June 30, 1940. The Nokes had two children - George and Robert. George was born in 1911 and died at the age of 15. Robert was born in 1923.]

As for re-enacting, a few of my friends and I have adopted the Dallas Guard Zouaves as our own. You might see us sometimes at Old City Park or at the Veterans' Day parade waving a 45 star flag and looking a little out of place. We are older and fatter than the originals, but we are a lot more dangerous, at leas to ourselves.

As I said at the beginning, this was a very uncolorful regiment, but something about that makes me like them all the more. Think about it. An entire Texas regiment that never intentionally hurt anyone. A Dallas regiment that spent its summer of war in Florida, baby sitting run-away kids and spotted pigs. If I ran things, we would put up a statue at the end of Elm Street of a young Spanish American War soldier, standing at parade rest and looking a little bored.

Information on the subsequent life of Roy Nokes was

provided by genealogist Larry N. Pumphrey of Los Angeles, CA