Maj. Gen. Shafter was the commander of the Fifth Army Corps, which served in the invasion of Cuba.

Background:

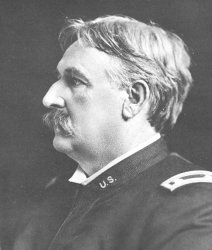

Maj. Gen. William Shafter

At the time that the American Civil War broke out, William Shafter was employed as a teacher. He enlisted in the Union army and was commissioned as a lieutenant in the 7th Michigan. He served at Ball's Bluff and later in the Seven Days Battles around Richmond, Virginia. During the latter, at the Battle of Fair Oaks, Shafter was in charge of the pioneers. Though slightly wounded, still he refused to leave his command. This was bought praise from his commanding officer, and eventually a Congressional Medal of Honor. Later in the war, he served in the American west as the major of the 19th Michigan. By 1864, Shafter was a colonel and was given command of the 17th U.S. Colored Infantry. By the time he left the service in 1865, Shafter was a brevet brigadier general of volunteers.

In 1867, William Shafter re-entered the military, securing a post as a lieutenant colonel in the regular army, eventually serving with the 24th U.S. Infantry on the frontier. In the post-Civil War army, promotion was slow. Shafter retained this position for ten years, from 1869 until 1879. In 1879, Shafter was promoted to full colonel, and placed in command of the 1st U.S. Infantry, and stayed with this command from 1879 until 1897. In the latter year, Shafter was finally promoted to brigadier general. The new rank brought a new command. This time, Shafter was placed in command of the Department of California.

With the outbreak of the Spanish American War, Shafter was appointed a major general of volunteers and assigned to the Fifth Corps, being organized in Tampa, Florida. One reason for his selection was his apparent lack of political ambitions. The Fifth Corps consisted mainly of U.S. regulars, though there were some volunteers,such as the 71st New York, and the "Rough Riders." By this time, Shafter, at age 63, was a corpulent three hundred pounds in weight and suffering from the gout. He was no condition to command troops in either Florida or in the jungles of Cuba. Visitors to his Fifth Corps camp commented that there seemed to be no discipline, though Shafter had the reputation of being a disciplinarian.

Though it was not the original intention to use the Fifth Corps in this manner, the corps was soon being hastily ferried to Cuba to begin an all-out assault on the island. The entire process of embarking, transporting and landing troops and supplies was disorganized, and generally occurred in spite of itself. The general was not provided with a proper staff, and was not able to handle all the necessary arrangements with the officers who served under him. Once Shafter finally had the troops loaded in sort of "free-for-all" manner, and with little direction on his part, orders were issued to Shafter, then aboard his headquarters ship, the SEGURANCA, delaying the assault . Shafter and his men languished for a week on the transports, baking in the sun, before the expedition steamed toward Cuba.

As the expedition, which in no way retained any element of secrecy, reached the Spanish coast, it was in some disarray and lacking full protection. Had the Spanish decided to mount an effort to prevent its progress, the expedition could have turned into a debacle.

Shafter was told by foreign military attaches that his task to invade Cuba was impossible. In spite of the odds, the beleaguered general began to formulate his plan. It was fairly simple, if undetailed. The U.S. public was not ready to face high casualties. Therefore, Shafter would try to surround Santiago and then demand surrender. This action would have to occur quickly, because, as Shafter knew, the summer and the disease-ridden rainy season would come all too soon. If the army wasstill on the island at that time, it may pay a terrible price.

Once Shafter was in Cuban waters, the senior naval commander in the area, Rear Admiral William Sampson paid a call on the general. The admiral was attempting to push his own plan of operations. The U.S. Navy had the Spanish fleet bottled up in Santiago harbor, however, with harbor entrance mined and the flanking, heavily- armed fortifications, the navy couldn't enter the harbor. The navy was pressing for Shafter's invasion force to attack the fortifications, to silence the guns and allow the mines to be removed. Then the navy would advance on the town itself. Shafter saw this plan as creating heavy casualties in the army, as the troops fought to the hilltop fortifications, while the glory of taking the city would go to the navy. Shafter was against this idea and stuck to his plan to surround the city. Unfortunately, neither man pressed the issue, resulting in a lack of understanding as to the true plan, and future bad blood between them.

Shafter and Sampson went ashore to meet with Cuban general Garcia. This journey required overcoming the cliffs which led to the rebels' headquarters, a major obstacle to the three hundred pound Shafter. A small but strong white mule was found to carry Shafter to the destination. The purpose of the meeting to try to co-ordinate of the all factions.

When the landing of the Fifth Corps was finally underway, the politically unwise and understandably stressed general made some abrupt remarks to reporter RichardHarding Davis when Davis complained that reporters where being kept from the landing. The words came back to haunt Shafter. He had drawn the ire of the reporters....and most never got over it, lambasting the general whenever possible. Shafter's reputation was not enhanced when he sent General Kent and his brigade intheir transports to feint a landing at Cabanas...and then forgot about the entire brigade for three days.

Meanwhile, Major General Shafter continued his with his plan to surround the city of Santiago. General Wheelerwas sent forward strictly to reconnoiter the planned route of the march toward the city and locate the Spanish positions. In disobedience of orders, Wheeler attacked. A skirmish occurred at Las Guasimas which bloodied the American forces. However, the Americans carried the day and Shafter said nothing about the disregard of orders.

In the meantime, Shafter was fighting a losing battle at his rear too - the landing of supplies. The landing point at Siboney was ill-suited to handle the off-loading of supplies. Little more could be landed other than rations and ammunition required to replace that used. The road from Siboney to the front was muddy and rutted, creating significant additional problems.

As reports came in of the impending arrival of Spanish reinforcements and supplies for Santiago, it became apparent to Shafter that he had to step up his attack on the city. He developed an attack plan that even he admitted was lacking in finesse. It called for General Lawton to attack El Caney, while the remainder of the troops attacked the heights in front of Santiago - San Juan Hill. Several diversionary attacks were also planned. The preparations were rushed and virtually no reserve was held back.

The plan began to go awry almost from the start. Though greatly outnumbered, the Spanish defenders of El Caney refused to give up the town. Lawton, unwisely, refusedto end his attack and simply block the Spaniards from joining their comrades in the defense of San Juan and Kettle Hills. The American troops from El Caney arrived at San Juan Hill too late to aid the attacking American forces. The American troops attacking the heights also got off to a very late start. Roads were crowded with men and materials of war. The Spanish kept up a fire that, though mainly by chance, was taking a toll. The American troops at the front could not withdraw, as the roads behind them were jammed. They could not stay in their positions, as they were taking heavy casualties. They could only attack. The famous charge on Kettle and San Juan Hills occurred and carried the day, mainly due to the tenacity of the American troops, and the sudden arrival of a battery of gatling guns. Shafter's plan had been too ambitious,did not take into account the tenacity of the Spanish defenders, and was too optimistic in the ability of Lawton's troops to take part in two engagements on schedule in a shortperiod of time. Also, as a side note, Shafter's action did nothing to aid the navy in its attempt to enter the harbor.

As the extent of the American losses were becoming known at Shafter's headquarters - his poor health and bulk did not allow him to go to the front so he stayed near Sevilla - both by report and by wagons delivering the wounded and dying to the poorly equipped nearby hospital, Shafter began to waver. He knew his troops' position was tenuous. The navy was doing nothing to relieve the pressure on the army, and his relations with Sampson were growing steadily worse. Supplies could not be delivered to the front, leaving his the men in want of necessities, such as food. Shafter himself was ill, and very weak. With this view of events, Shafter sent a dramatic message to Washington. He suggested that the army should withdrawal about five miles, giving upthe hard-won gains of the day.

Less than an hour later, one of Shafter's aides suggested another dramatic option. Why not ask the Spanish to surrender? Shafter, a man seemingly out of options himself, agreed that it should be tried. Oddly, as Shafter's suggestion of withdrawal, indicating both a political and military disaster, was arriving in Washington, he was also demanding the surrender of the city, an indication of an entirely opposite state of affairs. Shafter neglected to notify Washington of the surrender demand, compounding the problem. A short time later, with the naval battle of Santiago concluded, Shafter issued a message to Washington, leaving the impression that the Spanish had escaped....another disaster! The president and most of Washington only began to calm when Shafter belatedly informed them of his surrender demand and the reports of the resounding naval victory of the Battle of Santiago became known.

Meanwhile, negotiations to surrender the city began to occur in earnest through correspondence. Eventually, Shafter and Spanish General Toral met, and negotiated in person. Shafter was quite surprised when he found that not only was Toral surrendering the town, but also his troops in Guantanamo, San Luis and other areas. This meant he was surrendering 12,000 troops that were completely beyond Shafter'sreach. On July 17, the surrender occurred.

The surrender ceremony was marred by a bizarre incident. Sylvester Scovel, a correspondent for the New York World realized that it would be good publicity for him to appear in the many photos being taken of the flag raising on the roof of the palace, and found his way up. As the event was about to occur, he was found. He was ordered to leave, but would not. The officer in charge appealed to Shafter who responded "Throw him off!" Scovel escaped, but momentarily found his way to Shafter, who was still awaiting the formal flag raising. Scovel loudly exchanged words with the general and then took a swing at Shafter with his fist. Luckily, the punch missed. The day was further marred by Shafter's not having the navy represented through a combination of poor communications, partial oversight, and general lack of desire.

As the army continued its stay in Cuba, Shafter saw what he dreaded begin to occur. Disease began to rise. At first, Shafter did not truthfully explain the extent of the problem to his superiors in Washington, providing numbers which were fully half of the true number of men sick. Only when enough healthy men could not be found toperform basic functions in many of the regiments did Shafter begin to act. About eighty per cent of the men suffered from malaria, yellow fever or dysentery to some extent.

The government had its own concerns as the problem became clear. It would not ship the troops home, partially because it was concerned that when the true conditions of the war in Cuba and the problems of disease became public, it would effect the upcoming elections. There were also great fears of letting an epidemic of yellow fever loose in the U.S. On August 2, 1898, Shafter sent a cable to the secretary of war explaining how serious the loss of life could be if the troops were not removed from Cuba. The gravity of the situation caused the secretary to begin immediate work on the transfer.

Fearing that his late actions may not be enough to convince Washington, or fearing that they may not react quickly enough, Shafter became instrumental in another plan to alert those at home. The officers of the Fifth Corps almost unanimously were infavor of a rapid withdrawal. However, such a demand sent to Washington could be pigeon-holed. If it were leaked to the newspapers, public opinion would force thegovernment to act....but would cost the career of the officer who wrote the letter. After discussions, the effort was taken up by the most active non-career officer present - Theodore Roosevelt. Two letters addressed to Shafter were written by Roosevelt. One was circulated and signed by all of the officers, with Roosevelt bearing the brunt of any anger from Washington as the author. The second letter was a direct letter from Roosevelt to Shafter and was even more adamant than the "Round Robin" letter. By design, Shafter leaked both letters to the press.

Though efforts to begin the transfer had already occurred, the effect was electric. The letters became front page news across the country. Washington officials were seen in a bad light. Though Roosevelt felt the wrath of the War Department, Shafter's image was not improved either.

In September, Shafter himself finally left Cuba and arrived at Camp Wikoff, the quarantine camp on New York's Long Island. Here, on October 3, he announced the formal disbanding of the Fifth Corps.

Shafter continued to serve in the army after the war. His next command was back in California. He was now back in his former position as commander of the Department of California. This position was very important. Shafter, at San Francisco, was charged with directing the logistical and supply operations for the continuing campaign in Philippines. Unlike the virtual fiasco Shafter oversaw in Florida while mounting the campaign against Cuba, the operations to supply the Philippines went very well. Shafter did a very commendable job in his new position.

William Rufus Shafter retired from the army in 1901. He died in

California in 1906.

(As a service to our readers, clicking on title in red will take you to that book on Amazon.com)

Cohen, Stan. Images of Spanish American War, April-August,1998. (Missoula:Pictorial Histories Publishing Co., Inc., 1997).

Cosmas, Graham A., An Army for Empire : The United States Army in the Spanish American War. (Shippensburg, PA: White Mane Publishing Co., 1993).

Millis, Walter, The Martial Spirit. (Cambridge: The Riverside Press, 1931)..

Nofi, Albert A., The Spanish-American War, 1898 . (Conshohocken, PA: Combined Books, 1996).

Scott, Col. Robert N., ed., The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. (Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1884, Series I, Vol. XI, Part I).